Techno-economic protagonism: Ontology

Theoretical foundations and method for qualitative digital power analysis

Update (May 8, 2024): This article is also available at: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4818443

Update (May 10, 2024): A code repository is now available with the latest versions of the Annex 1 LLM prompt, Digital Powercube instructions, and standalone TEP analysis LLM prompt. Access it here: https://github.com/antoniomaxai/Digital-Powercube-Prompts/

Abstract. Techno-economic protagonism (TEP) is a new conceptual metric that builds on classic notions of soft power to analyze Digital Power dynamics between contemporary states. Drawing on Joseph Nye's classification of soft power and John Gaventa's Powercube framework, this article introduces TEP as a qualitative indicator portrayed as a new layer of Nye’s soft power and by superimposing this new layer on Gaventa's Powercube. The proposition illustrates a way to define and visualize Digital Power properties, contributing to the ongoing discussion on digital statecraft characteristics and providing a tool for the analysis of nation-state level Digital Power projection dynamics in the AI era.

Contents

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and motivation

1.2. Objectives

2. TEP as a concept

2.1. On power and power projection

2.2. TEP and soft power

2.3. The Powercube

2.4. Big Tech politics

2.5. Techno-economic strategies

3. The digital realpolitik arena

3.1. Mapping geopolitical TEP dynamics

4. Qualifying techno-economic dynamics

5. Conclusion

5.1. Implications for the digital statecraft

5.2. Limitations and future research directions

Annex 1 - Using the Digital Powercube with LLMs

Annex 2 - Sample data of the Digital Powercube analysis with LLMs

1. Introduction

While the societal impacts of digital technologies and artificial intelligence have garnered significant attention, there remains a crucial gap in contemporary Science and Technology Studies (STS) discourse regarding the cultural lag between techno-economic power dynamics and the evolving landscape of power projection. Although various scholars have explored concepts such as digital soft power, the transnational reach of national techno-economic champions, and the potential risks posed by AI to democracies, labor, and social welfare, these analyses frequently fail to capture the intricate interplay between technological prowess and the shifting paradigms of contemporary nation-state power projection.

1.1 Background and motivation

When I developed the idea of TEP, my first intention was for it to fit as a qualitative metric or indicator that clarifies how the interplay of powerful digital infrastructure and its economical incentives, particularly oriented at AI efforts, impacts traditional statecraft. In my view, left in the shadow of vague narratives, myopic strategies may potentially become more damaging to digital states than they should.

The existing literature, though insightful, often falls short of providing a holistic framework that adequately encapsulates the multifaceted nature of this phenomenon. Consequently, there is a pressing need for a more comprehensive examination of how the rapid evolution of techno-economic capabilities is reshaping the traditional dynamics of power projection among nation-states. This deficit in scholarly inquiry becomes increasingly pronounced as we venture deeper into the era of AI, where the mastery of this transformative technology holds profound implications for the future dynamics of global influence itself.

1.2 Objectives

By identifying and addressing the digital soft power characterization gap, TEP can contribute to a clearer understanding of the intricate relationship between true digital sovereignty and the digital state strategic planning. TEP was made to be a simplified yet efficient construct oriented to understand complex techno-economic power dynamics, aiming to equip policymakers, academia and other stakeholders with invaluable insights, enabling wider foresight.

2. TEP as a concept

Techno-economic protagonism, the term, is the fusion of three distinct concepts into one: power projection, tech giants political reach and their home countries’ successful adaptation to strategic shortcomings, that historically, could enable competition to strive and sometimes, even bring critical damage to their own domestic markets. This chapter covers these three topics, assuring TEPs terminology is properly grounded.

2.1 On power and power projection

Many great authors such as Foucault, Dahl, Weber, Kaplan, Gramsci, Keohane, Lukes and Bertrand Russel, to name a few, have quite relevant works that in one way or the other address power, its dynamics and outcomes. As a greatly contested concept, power analysis has many moving parts, relying on resources, context, elements and behaviors. Here, I rely mostly on the works of professors John Gaventa and Joseph Nye to build TEPs narrative, both notorious scholars whose extensive works on power should serve as foundation for my vision of power as TEP aims to isolate.

TEP illustrates how a group of techno-economic assets, enablers of today and tomorrow's sovereign AI platforms, can assist a country’s soft power projection both internally (between government and people, or I-soft power) and externally (power carried from one society to the external world, or E-soft power)(Chitty, 20141). And to understand why TEP specifically advocates for a “new era of soft power,” it is then proper to distinguish between soft power and other popular classifications of power.

Nye’s soft power is a well known contrast to the Yale’s political scientist Robert Dahl’s coercive power, that in the words of Nye: “focuses on the ability to get others to act in ways that are contrary to their initial preferences and strategies”2. Hard power is an overt command, a crystalline relation of power in the open, it is a strong statement, such as those of a parent telling a kid not to do something: both sides feel this power, the kids’ initial preferences were diverted by the power, and an asymmetric relation is formed. Military power and the use of force by the state may also be coercive, a power that is used to induce others to do what they otherwise would not. These are examples of hard power.

Soft power on the other hand, was first introduced by Nye as an academic concept, as a thought experiment to fill a deficiency in the way international relations scholars thought about power3. The concept was created to illustrate how power dynamics can happen via attraction instead of coercion. In the words of Nye: “hard power is push; soft power is pull”4.

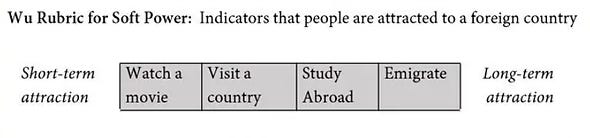

These simplified definitions assume some familiarity with power dynamics as understood in Political Science and International Relations, but for this articles’ purpose, it is sufficient to understand that hard power refers to the use of behavioral coercion, while soft power is more of a conditional manipulation and that such manifestations of power can be exercised by a nation both domestically and internationally to influence those within its sphere of influence. But to further clarify how soft power relates to statecraft, I believe I can rely on Georgetown’s professor Irene Wu’s5 well-known rubric for soft power measuring:

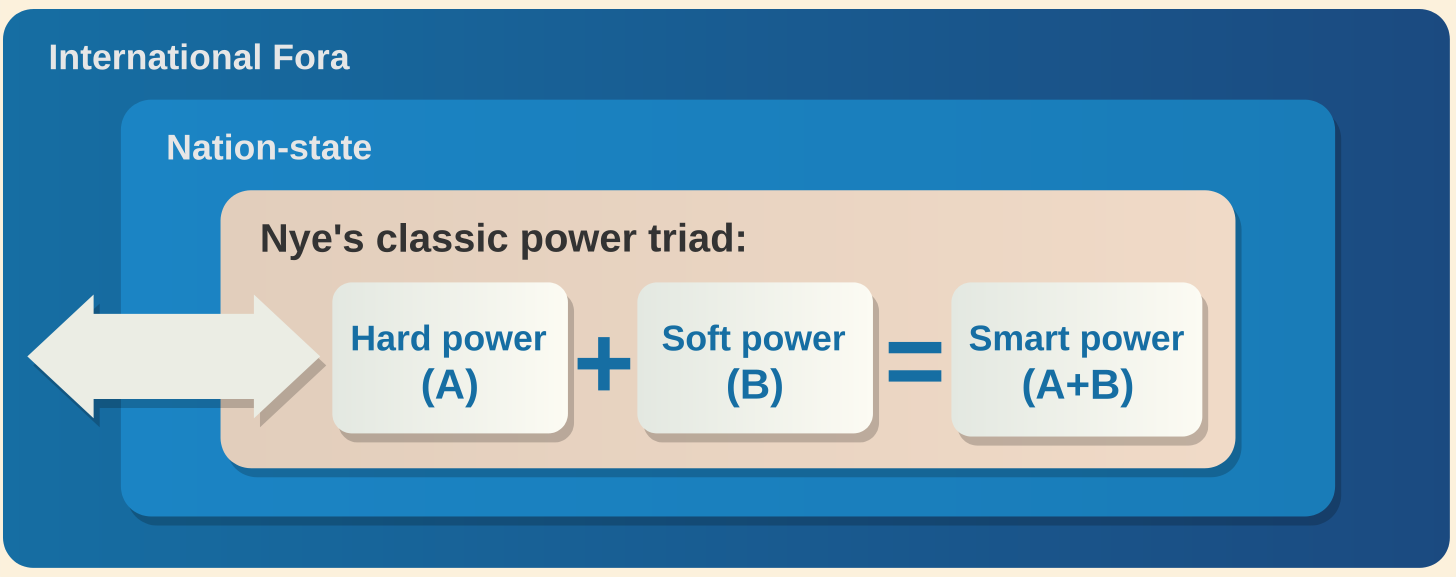

Nye is also well-known for creating the concept of “Smart power,” which refers to the strategic combination of hard power coercion and soft power persuasion in statecraft strategic reasoning. And at this point, his classic representations of power can be visualized as so:

Before the concept of techno-economic protagonism emerged, I was with Nye’s in seeing the manifestation of the power projected by digital platforms as simply another medium for classic examples of media as vehicle for soft power projection: we stream on Netflix the same movies cable companies used to play, we stream on Apple Music the same songs that the Millennials generation used to buy via CDs and we all buy same shoes on some website after seeing some celebrity wearing them. Soft power online works the same as ever did on TV or the radio: with a nudge6. So the question is: what changed?

Several authors note that as a generation, we are witnessing a great power diffusion away from states to non-state actors7. Apple, the American technology company, is worth more in 2024 than entire nations8. Similarly, Instagram, also a product of yet another American tech leader, can easily own more data of a nation’s people than their own government ever did9. These companies are no longer just intermediaries of American values and culture, they have become international actors in their own right, a reflection of their massive digital impact and business aspirations. Indeed, as early as of 2013, scholars were already describing them as a “meta-power”10.

A decade later, we now have not only AI in its weakest form as it ever will be, we also have massive data processing capabilities as the world has never witnessed, a digital infrastructure so massive that could well be considered as assets of power influence. However, concerns surrounding the ethical implications, potential biases, and potential overreach within these advancements are not novel, scholars and other researchers have been actively exploring these issues since the rise of this Platform Capitalism11 in the early 2000s.

Nye was already in 2014 describing Cyberpower behavioral characteristics as “the ability to obtain preferred outcomes through the use of electronically interconnected information resources of the cyberdomain”12, a quite assertive definition of a virtual soft power persuasion. But in defining what Cyberpower mean, he was dealing with the world in front of him, not the hypotheticals on what the Artificial Intelligence world would eventually become in 2024.

2.2 TEP and soft power

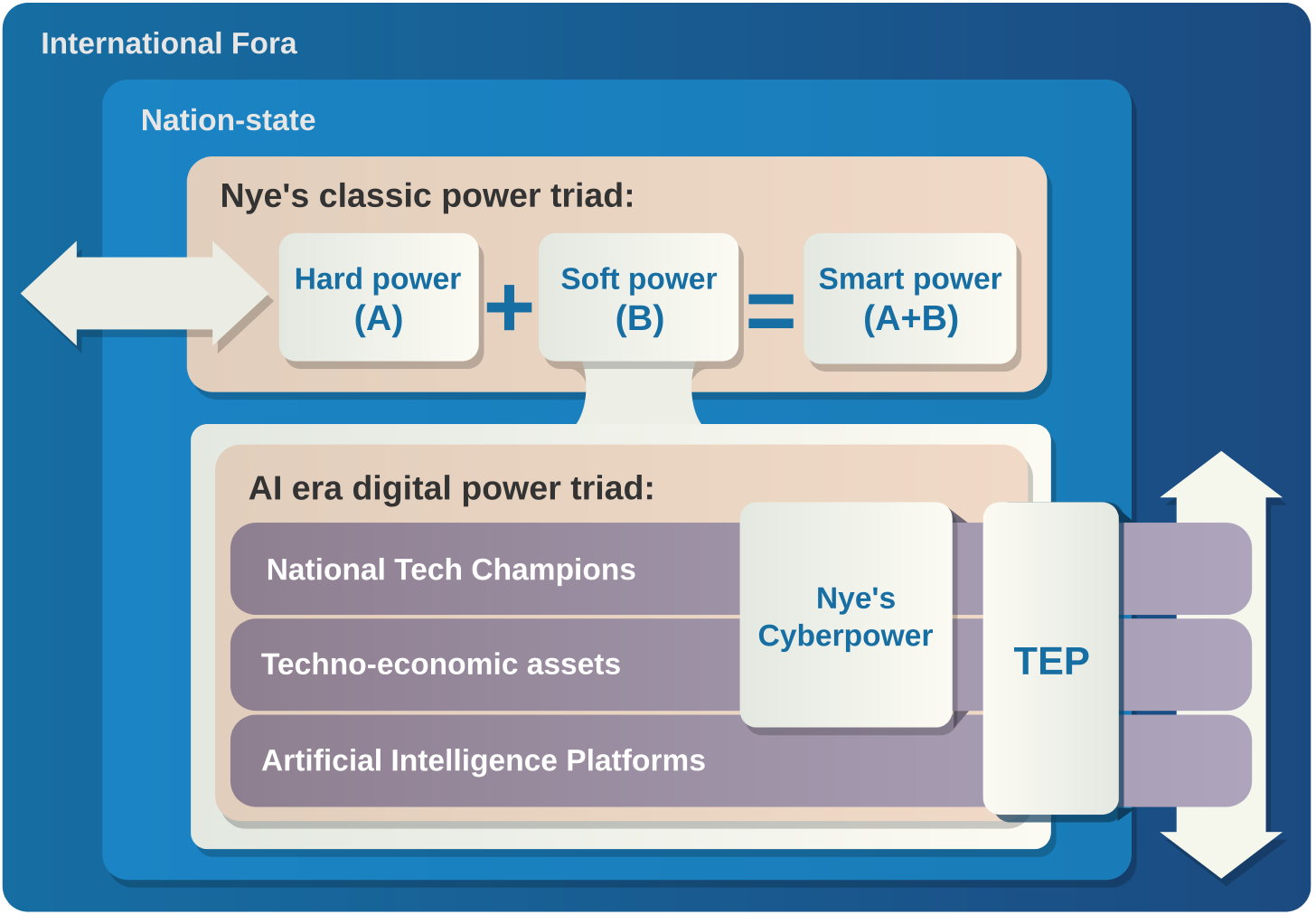

I argue that today’s trinity of tech giants, AI platforms, and their underlying digital infrastructure represents a novel form of digital power that transcends the mere digitization of traditional media and classic soft power projection dynamics: While this view might have held true over the past decade, it no longer captures reality.

Here, my reasoning relies on the fact that today’s advanced AI systems already mimic human capabilities, replicating the work of hundreds of specialists or even entire companies in fractions of time and cost. As AI continues to scale, this disparity will likely widen into nation sized disparities, expanding the depth of this divide between “AI have/have-not” nations. Such trinity of a nation’s digital capabilities should then be measurable, and most of all, understood as an analytical unit, particularly through the lenses of AI, in order to tackle the upcoming issue of global automation-driven capacities (and inequality,) between nations.

TEP recognizes that traditional soft power dynamics persist in today’s world, but posits that this combined digital power constitutes a distinct axis of influence that extends beyond the digital sphere, impacting real-world outcomes. Notably, techno-economic autonomy is nowadays an active topic (and target) of national economic strategies13, exerting substantial pressure on the competition of already established businesses and raising barriers for new market entrants. This phenomenon blurs the lines between soft and hard power, highlighting the complex interplay between economic influence (and coercion?,) and geopolitical strategies of digital nature. TEP not only raises awareness to these dynamics, but also attempts to isolate them amid the noise of other initiatives. TEP characterization of this digital power can then be visualized as so:

Nye’s characterization of Cyberpower is then included to illustrate his definition: “Cyberpower can be defined in terms of a set of resources that relate to the creation, control, and communication of electronic and computer-based information—infrastructure, networks, software, human skills”14. But to understand and characterize Cyberpower without directly addressing what I term in Figure 3 as “Tech champions”, overlooks the state-level economic might these actors wield in the contemporary political fora. This, coupled with the capacity multiplier introduced by today’s AI platforms, suggests we are about to witness a significant transformation in the power projection capabilities of AI-capable nations. So as illustrated in Figure 3, such combined digital might then constitutes a distinct digital power projection trait that, thanks to its innate digital nature, transcends nation-state borders with unseen speed, forging entirely novel projection capabilities.

The relationship between digital power and classic soft power constructs creates a scenario where primacy (dominance) reinforces traditional techno-economic power dynamics. Consequently, this scenario fosters digital subservience and digital leadership, characterizing the dimensions of digital power that the concept of Techno-Economic Protagonism seeks to isolate and analyze.

In order to demonstrate the multidimensional aspects of power relations and see how this new digital power layer introduced by TEP addresses contemporary dynamics, a visual framework for power analysis is introduced and revisited.

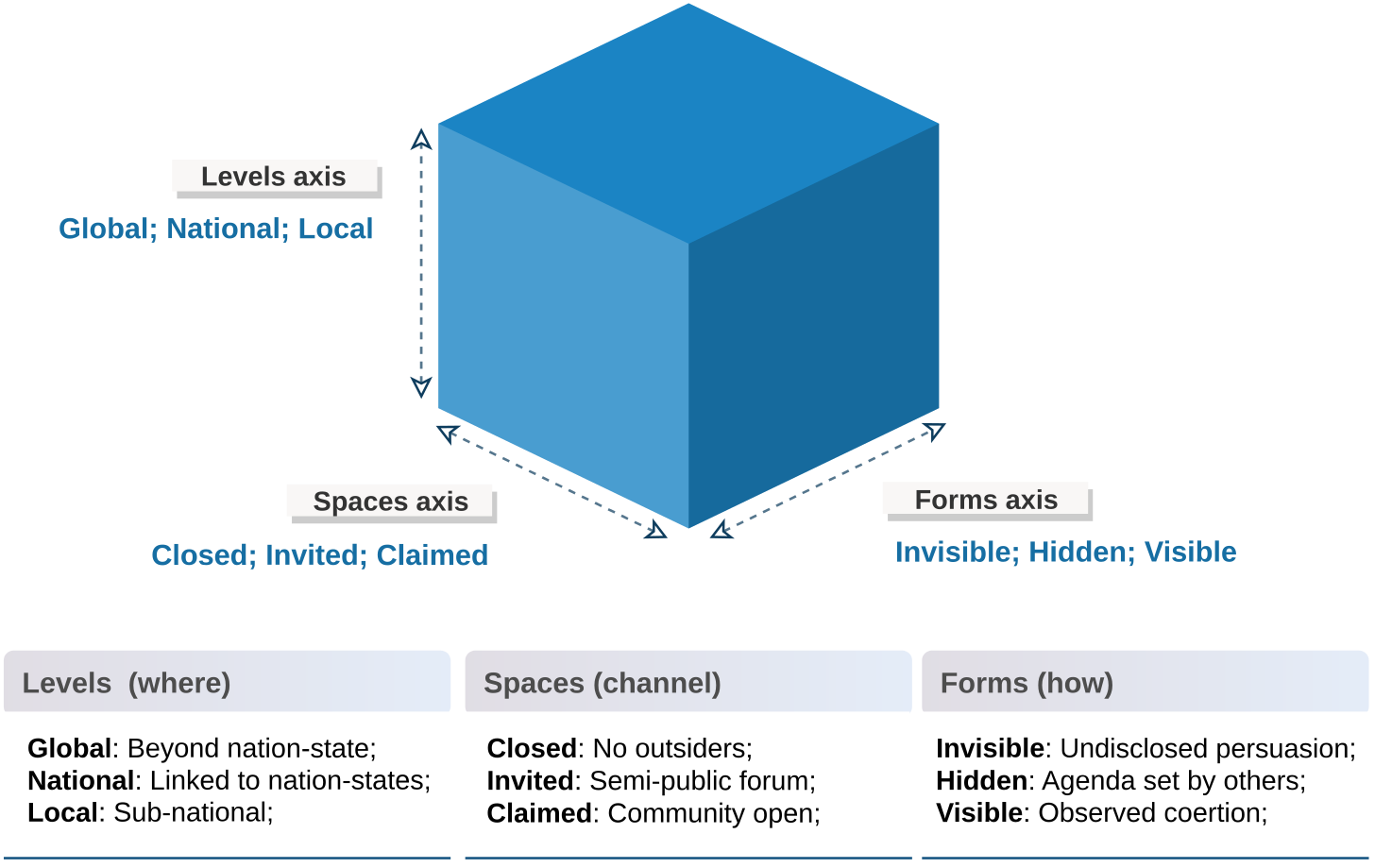

2.3 The Powercube

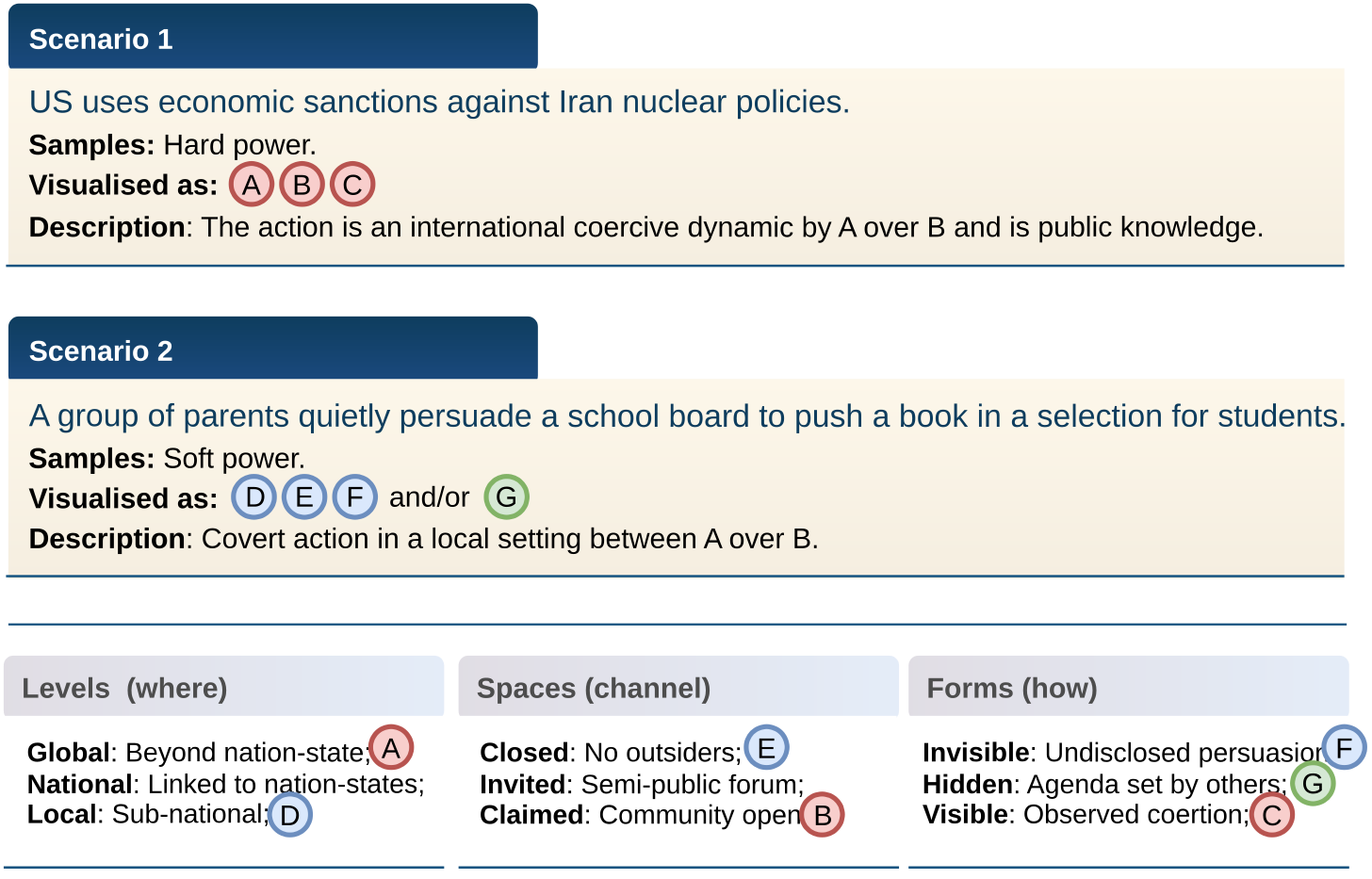

Building on the work of his professor, Steven Lukes, who identified three dimensions of power — namely: visible (akin to Joseph Nye's hard power), hidden, and invisible (akin to Nye's soft power, also known as Lukes' “third face of power”) — John Gaventa realized that Lukes dimensions, while forming a continuum, reflected only one aspect of power, so he proposed a framework that can be applied to seize how power manifests itself differently in different spaces. The Powercube is the outcome of his effort15.

Steven Lukes suggests the Powercube can be seen as a “theory frame”16, as an analytical tool to “shed a light on an old problem”, but the fact is that scholars across the globe have used the Powercube to this day in order to understand power dynamics across all its three dimensions, in order to discuss civic participation, policy and governance issues in several fields including: digital inclusion, economic justice, environmental issues, trade, human rights, among many others17. Figure 5 illustrates two fictitious power dynamics anecdotes to sample the Powercube capabilities for this article.

The analytical capabilities of the Powercube framework can be used to understand how hard and soft power multidimensional dynamics take place in virtually any scenario. Such capability will be explored to analyze TEP dynamics in Chapter 4.

2.4 Big Tech politics

British professor Susan Strange, also happened to have her own version of hard and soft power narratives. In her writings (Strange, 1998) she defined “Relational power” quite the same as other conventional narratives of hard power: “the power of A to get B to do something they would not otherwise do”18. And for her, “Structural power” is more than the power to set the agenda of a discussion or to design rules and customs, but is also “the power to shape and determine the structures of the global political economy within which other states have to operate”19. For her, the surrounding structure of a relationship would determine the relative power of the parts. Her distinction reflects her attempt to draw attention to power in the political economy, as opposed to seeing economic power and political power as separated units.

Strange’s focus on structures and political economy surely highlights the importance of these matters on the role that national tech champions have on both these forces thanks to their scale and influence of digital structures. For her, “Structural power” lies with those in position to exercise control, and sources of such power are “control over security, control over production, control over credit and control over knowledge, beliefs and ideas”20. Alas, not a single one of these isn’t touched by 2024’s big tech, or how Strange called similar enterprises, “transnational corporations (TNCs)”.

And it was thanks to Strange’s focus on economics that TEP has its economic bit. In Strange’s “The Retreat of the State: The Diffusion of Power in the World Economy” she characterizes the techno-economic role of “TNCs” and to quote her narrative is paramount to solidify how TEP understands big tech as protagonists of the digital power construct and operation21:

A major hypothesis of this book is that the shift from state to markets has actually made political players of the TNCs. The argument is not that they influence the foreign policies of states or are, in any general and important sense, the 'powers behind the throne', even though in special circumstances they may be so. Rather, it is that they themselves are political institutions, having political relations with civil society. [...] The paradox is that this has not happened entirely by accident. [...] It was not that the TNCs stole or purloined power from the government of states. It was handed to them on a plate - and, moreover, for 'reasons of state'. [...] States are legally and conventionally defined by the territorial limits of their authority. [...] When the shift of power is to other authorities - authorities whose basis is not their command over territory but their command over the nature, location and manner of production and distribution of goods and services, this clearly raises some new questions about the nature of sovereignty and the dispersion of power and political control. (Strange, 1996, 44-45)

Remarkably clean in Strange’s words, is the knowledge that today’s enterprises have a political grip of their own, where these are not only responsible for creating state-of-the-art technologies, but they also play a very active role in lawmaking, lobby, regulations, geopolitical strategies, and of course, in the very own power projection of their home nation’s socioeconomic interests and influence capabilities.

Here I not only agree with Strange’s thoughts in a definitive manner, I also decide to end any pondering about tech giants role in politics and I take it as an axiom that does sounds better in the words of internet governance superstar scholar Laura DeNardis22:

“Arrangements of technical architecture are also arrangements of power.” ( DeNardis, 2014).

2.5 Techno-economic strategies

The final aspect of TEP conceptualization is about the depiction of the competition among countries for digital primacy, particularly those that can leverage their tech champions to install digital behemoths and monopolies in techno-economic activities. While it may seem obvious that the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) domain is highly competitive, there are a few key axioms in this industry that warrant closer attention. To provide a comprehensive understanding of TEP, I turn to the insights of yet another economics scholar to close out TEP conceptual ontology.

In her paper titled “Leapfrogging in international competition: A theory of cycles in national technological leadership,” Professor Elise Brezis (Brezis et al., 1993) concludes with a short but quite strong principle: “Those who have a great deal of experience with an old technology may, for that very reason, fail to take advantage of new opportunities”23, or in other words: success may breed failure.

The argument of this piece is that what some may perceive as shortsightedness in the adoption of new endeavors can actually be a rational decision by entrepreneurs, as the benefits of maintaining the status quo can be very attractive. However, Brezis et al.’s theory presents a model that clarifies how competitors view others’ complacency: as an opportunity. This paper states that24:

“Endogenous-growth theory suggests that technological change tends to reinforce the position of the leading nations. Yet sometimes this leadership role shifts. We suggest a mechanism that explains this pattern of "leapfrogging" as a response to occasional major changes in technology. When such a change occurs, the new technology does not initially seem to be an improvement for leading nations, given their extensive experience with older technologies. Lagging nations have less experience; the new technique allows them to use their lower wages to enter the market. If the new technique proves more productive than the old,

leapfrogging of leadership occurs.” (Brezis et al., 1993)

The model presented in this paper differs from traditional industrial-organization literature by focusing on the role of state-level misread capabilities. Specifically, the authors argue that firms in a leading country may fail to adopt a new technology because, from an individual firm’s perspective, the technology may initially appear inferior in a country with extensive collective experience in older techniques. This unique perspective sheds light on how misreading capabilities at the state level can impact technological adoption and innovation itself.

Hence, it may appear that lagging countries failing to adopt AI or prioritize true digital sovereignty may be falling into such a trap, allowing established digital monopolies to thrive. However, current tech leaders and their home countries seem to have successfully avoided a “leapfrogging” scenario in the run for AI. While this could be attributed to good governance and strategic planning, an alternative perspective is that such “victory” may in fact be the outcome of prioritizing smart insulation over innovation, by imposing tech champions investment capabilities as “tech shield”. This raises the question of how nations can technologically insulate themselves in the AI era. The answer, in my view, lies in the concept of Techno-Economic Protagonism.

By establishing techno-economic primacy as a foundation for their nation's welfare, leading digital states can ensure that their long-term strategies are built on a solid base that enables them to maintain their status quo, keep competition at bay, and prevent brain drain, sustaining their pace of innovation over the long term. In other words, by insulating their techno-economic development and leadership, countries can create a virtuous cycle that reinforces their competitive advantages and bolster ongoing innovation competences, without the need to chase innovation.

However, it is in recognizing these pragmatic dynamics as the defining characteristic of protagonist countries, as opposed to background actors playing supporting roles or mere extras in the digital scene geopolitics, that the foundational concept of what I have chosen to call Techno-Economic Protagonism emerges.

At this point, TEP’s overall concept should be aligned with the competitive dynamics of digital power. However, as a framework, TEP would also benefit from a clear and defined world-building scheme. The next chapter elaborates on how I perceive the current geopolitical tech arena, aiming to crystallize TEP as a metric for evaluating factual digital state protagonism traits within its overarching ontology.

3. The digital realpolitik arena

From a strategic standpoint, countries in position to do so can adopt digital doctrines that provide them with a set of tenets oriented at maintaining tech leadership while also constraining digital adversaries’ range of possibilities to question said leadership. And that’s what renowned scholar Robert Atkinson exemplified when he published his article titled “A U.S. Grand Strategy for the Global Digital Economy” (Atkinson, 2021). In this work Atkinson calls for a doctrine he frames as one of a “digital realpolitik”, an overarching strategy with fierce focus on maintaining U.S. global tech leadership that also puts forward a set of principles aimed at this end25:

It is not a surprise that leading tech nations have hegemonic aspirations, it is a well known fact that those at the top won’t legislate or scheme against their own status, but to understand this mindset of loss avoidance is to understand the pragmatism of the AI era power dynamics and the competitive nature surrounding the tech arena.

In such an arena, National AI strategies are but a piece of this puzzle. Not only these documents aspirations face the hard problem of making it through from A to B, actually delivering its propositions, but at the same time these also have to deal with hegemonic aspirations of leading nations, such as of those proposed by Atkinson for the United States, and of course, avoid the leadership traps of innovation cycles, as illustrated by Brezis et al.

One particularly concise approach to navigate these contemporary techno-economic dynamics should then be to make sure digital infrastructure assets are truly sovereign, no matter if private or state owned. Concise because we see nowadays how the topic of de-risking policies, decoupling strategies, and even more assertive propositions in the shape of a “Digital Autarky”, of “Techno-Nationalism” and “Strategic Autonomy,” doctrines have become common topics in conversations about the statecraft arts for the digital state. So how can nations seize and understand these dynamics in order to empower statecraft with the necessary foresight for informed progress?

My answer is then to propose that the inherent asymmetry between nations that have vital assets to pursue their own digital sovereignty and those who may aspire the same ideals but lack vision and/or structure to actually deliver, should eventually characterize a scenario of digital power competition between potential digital hegemonies and those who merely orbit such aspiration.

3.1 Mapping geopolitical TEP dynamics

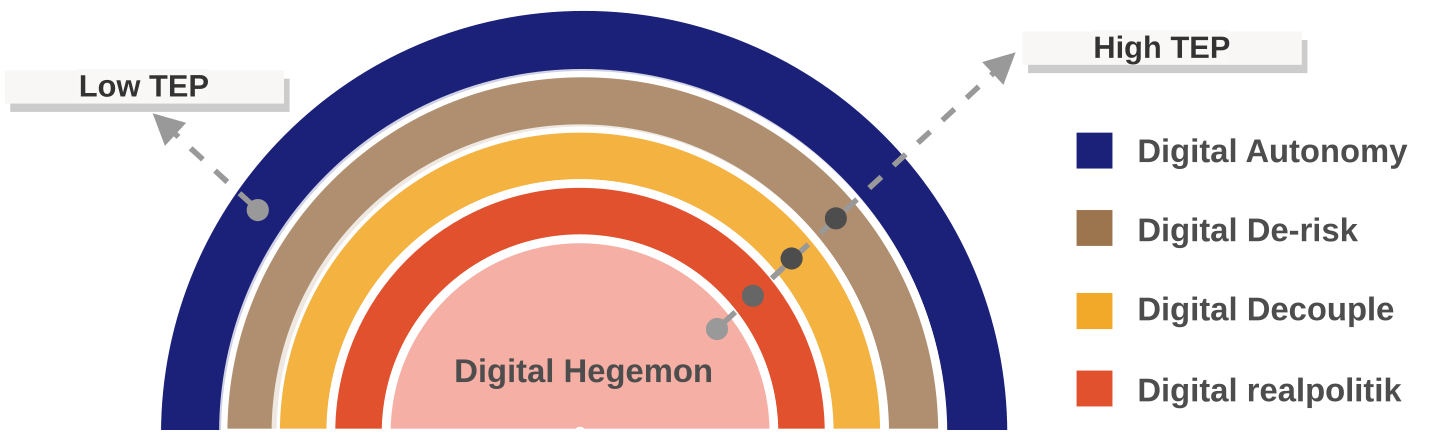

As a qualitative metric, TEP then assumes that evident asymmetry between those that have sovereign digital capabilities and those that depend on commercial relations coming from truly sovereign digital states, characterizes what I understand as High TEP and Low TEP relation from nation A towards nation B. A qualification that can be visualized as so:

Closer to the center (Figure 6), lie nations that can not only assure their own autonomy in digital affairs, but can also project distinct levels of this autonomy and digital sovereignty onto other nations, a Digital Power, if you will. Nation-states under commercial or political dependence to have access to infrastructure and services of digital nature from others, characterize a relationship of interdependence. This dependence lowers their own TEP score, while simultaneously strengthening the TEP of the nations providing these services.

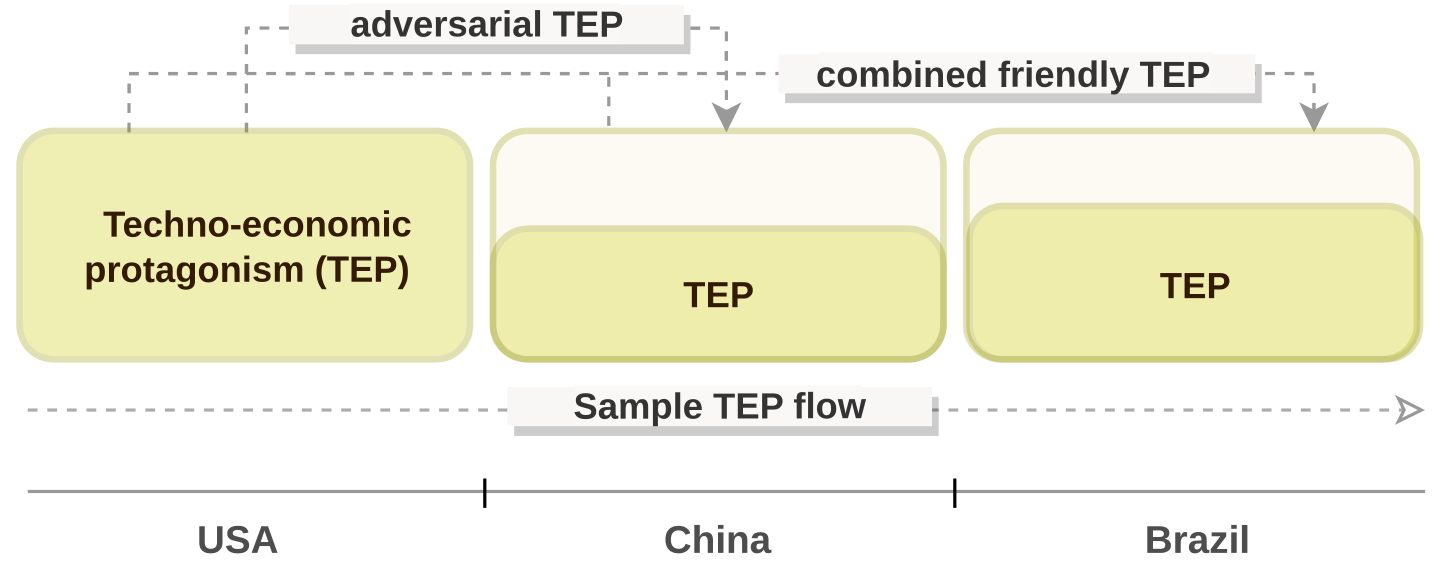

And thanks to the state level adversarial nature of digital leadership, geopolitical constraints and even economic strategies, such a system also influences the TEP of nations under adversarial stress. This dynamic can be visualized as so:

Illustrated in Figure 7 is an anecdotal flow to illustrate TEP asymmetry between China and Brazil. China is undoubtedly a digital champion nation, vastly more capable in technological firepower than Brazil is as of today. But as the United States projects its TEP over China in a more adversarial approach (via export controls, de-risking policies, sheer adversarial mindset, etc.,) than it does to Brazil, we can visualize how Brazil’s TEP benefits from the competition of others. And as this country enjoys friendly techno-economic relations with both nations, here, its combined TEP excels over nations under more adversarial TEP pressure.

Although efforts are underway to validate TEP as a quantitative metric, at present, its qualitative assessment can be performed by examining digital interdependence and projection capabilities that exist between nations offering digital sovereignty and platforms, and those bound by reliance or significant commercial ties with the former. In order to illustrate current TEP capabilities, a framework to characterize these dynamics is introduced in the next chapter.

4. Qualifying techno-economic dynamics

As 2024 AI capabilities already impose a new momentum of digital statecraft, true sovereignty of cutting-edge infrastructure and technologies now also appear to play a crucial role in shaping global influence. In this uncharted terrain, TEP can be used to raise awareness of techno-economic dynamics, particularly in understanding the interdependence effects of current and future AI platforms as assets of true digital sovereignty, adding to the contemporary arsenal of a nation’s digital soft power.

To analyze TEP dynamics between countries, we first need to define a digital power projection relationship. As discussed in Chapter 2.3, Gaventa's Powercube (Figure 4) helps categorize traditional power dynamics. And as shown in (Figure 3,) TEP accommodates itself as an independent layer of soft power dynamics, specific for the framing of digital power interdependence and projection.

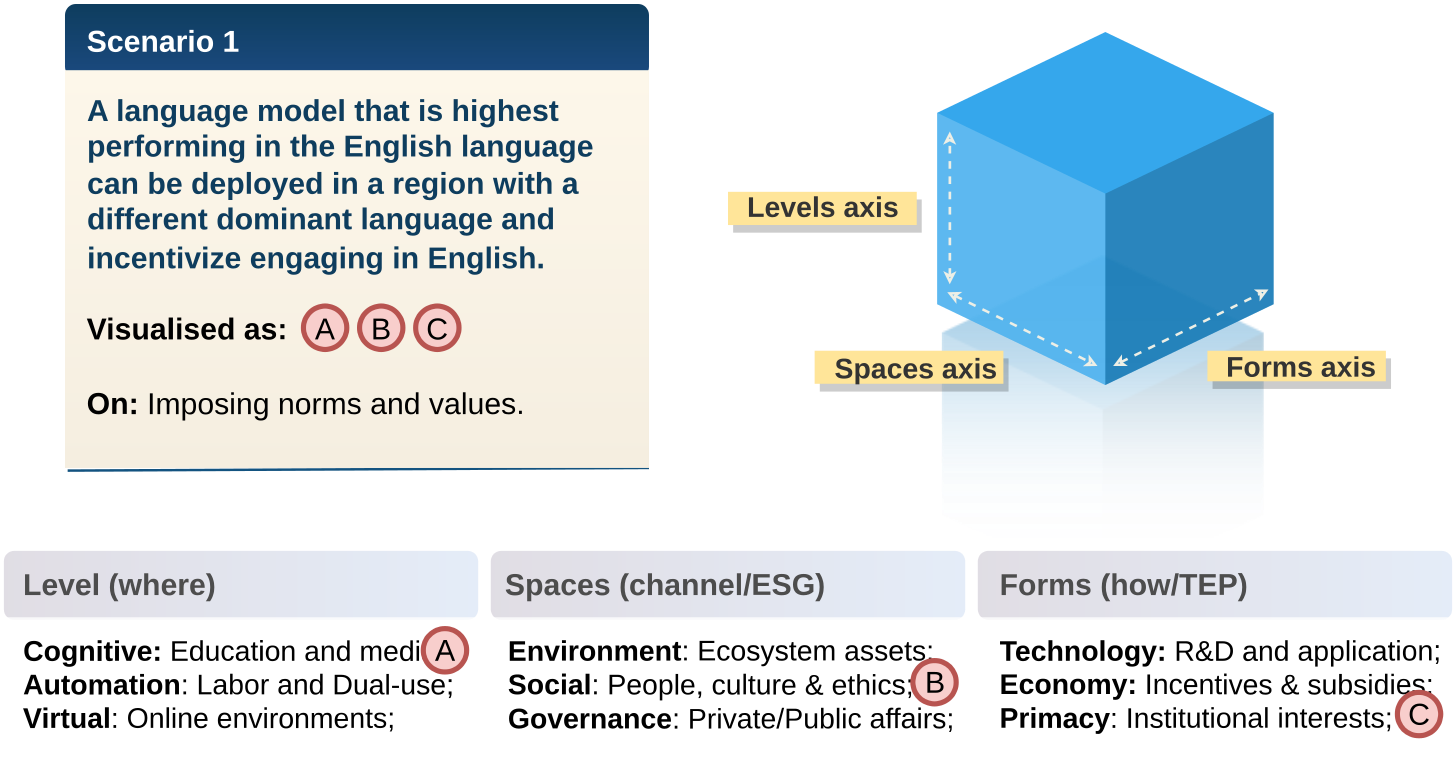

Building on the Powercube framework, I then propose the “Digital Powercube” to materialize this new layer as a framework for techno-economic relations analysis. While the traditional Powercube remains valuable for assessing conventional power definitions, as an anecdote to virtual environments that exist on top of real world experiences, the Digital Powercube is then superimposed over the Powercube, with specific focus on characterizing TEP projection dynamics.

The Digital Powercube diagram (Figure 8) differs from its traditional counterpart in its distinct axes specifications. These axes represent the Levels at which TEP influence takes place, the Spaces impacted (or channels through which the influence is exerted), and the Forms (or mechanisms through which a TEP relationship takes place). In this depiction, TEP is an axis of its own, linking its terminology to the instrumentation of digital power analytics.

The first axis, “Levels,” delineates the domains where TEP exerts its influence, spanning the A) Cognitive (knowledge, education and media), B) Labor automation (in industrial, technological and dual-use/defense settings), and C) Virtual (online environments such as platforms, apps and mixed reality realms).

The second axis, “Spaces,” identifies the specific channels or spheres through which TEP manifests its effects. Drawing from the well-established Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors, this axis provides a recognizable taxonomy for mapping TEP’s impact across the elements of this axis, namely A) Environment (the environment, natural resources, goods/products/services and supply chains), B) Social dynamics (People, culture and ethics), and C) Governance structures (Private/Public affairs, the logistics of a business or government).

The third axis, “Forms,” elucidates the mechanisms driving TEP's operations, encompassing A) Technology (technological research, development and deployment), B) Economy (economic strategies rooted in institutional or sovereign interests, incentives and subsidies), and C) Primacy (the strategic pursuit of digital supremacy — an aspiration reflecting both private sector and state ambitions).

A sample Digital Powercube analysis is displayed in Figure 9 illustrating its capabilities. Additional demonstrations of its analysis are included in the Annex 2.

5. Conclusion

Techno-economic protagonism (TEP) offers a novel normative metric for classifying and analyzing techno-economic soft power relations of digital nature. It provides a common analytical perspective to identify key manifestations of power in relations of digital protagonism or dependence, facilitating a comprehensive analysis of digital power dynamics across a number of domains.

The introduction of the Digital Powercube framework expands upon well-established power dynamics analysis tools and offers a novel instrument for characterizing the techno-economic impacts on nation-states in the AI era. This framework empowers analysts with a systematic and structured approach to comprehend contemporary aspirations of digital sovereignty matters. Ultimately, TEP and the Digital Powercube introduce a standardized language for depicting the interplay of power dynamics in digital affairs, paving the way for a more grounded characterization of digital state traits and shortcomings in the modern power arena.

5.1 Implications for the digital statecraft

The current lack of a standardized approach for analyzing techno-economic dependence allows these dynamics to remain obscure or vaguely discussed. This enables disparate narratives and inconsistent terminology to persist, and over time, hinder an unified and efficiently aligned social sciences perspective.

TEP addresses this need by providing a common language to analyze these relationships. However, its increased precision may eventually reveal uncomfortable power dynamics, potentially straining current international relations.

Further digital power research using TEP and the Digital Powercube framework may impact future contracts, strategies and discussions surrounding digital power relations of servitude or leadership.

5.2 Limitations and future research directions

It is relevant to clarify that while understanding TEP relations of digital power projection can identify potential risks, neither TEP or the Digital Powercube are risk assessment frameworks.

Further exploration of additional dimensions of the Digital Powercube and combinations of the TEP metric with other frameworks may reveal hidden relations and dynamics not covered in this article, aiding future analysis.

While TEP attempts to be holistic, potential blind spots in the complex dynamics of state level techno-economic relations may become evident over time.

Annex 1 - Using the Digital Powercube with LLMs

A sample prompt to explore the Digital Powercube framework capabilities with Large Language Models is provided next. As most LLMs are currently capable of inferring on the proposition described in the prompt, resulting responses should demonstrate how specific challenges can be described by a TEP analysis.

The provided v1.1 version of the prompt specifically requests the LLM to employ a basic confidence level scoring scheme for its responses, but TEP analysis isn’t tied to a specific scoring system. Researchers are encouraged to investigate this capability using their own data and alternative methods to further develop and explore TEP analytical boundaries.

As an anecdote, during my tests, LLM replies on different commercially available LLMs were by a good margin consistent for the same problem/questions. And while LLMs can’t be trusted for empirical analysis, the prompts can efficiently demonstrate Digital Powercube capabilities in providing standardized digital power analysis material.

Instructions:

Copy and paste the provided full prompt in any LLM. After the first response to the full prompt, you may use the shorter prompt as illustrated in the Note 1 with your own custom problems/questions.

Note 1: Subsequent tests may ignore the first full prompt (in the same conversation) and just ask the LLM for the analysis of any singular proposition using the Digital Powercube framework as so:

Using the Digital Powercube framework as introduced earlier, give me your analysis for the following problem:

"A language model that is highest performing in the English language can be deployed in a region with a different dominant language and incentivize engaging in English"Full prompt for TEP analysis using the Digital Powercube (v.1.1):

Antonio Max's Techno-economic protagonism (TEP) is a new conceptual metric that builds on classic notions of soft power to analyze "digital power dynamics" between contemporary nation-states (A relationship of power between country A and country B, state level tier relations). Drawing on Joseph Nye's classification of soft power and John Gaventa's Powercube framework, TEP is a qualitative indicator. As such, a TEP analysis provides a normative power projection context for classifying and explaining techno-economic soft power relations.

The Digital Powercube is this new layer superimposed over Gaventa's Powercube, a novel framework for techno-economic relations analysis with distinct axes specifications of its counterpart. The Digital Powecube axes categories are oriented towards exploring how digital power impacts the real world, performing a TEP analysis in characterising digital power projection and impacts.

Understanding John Gaventa's Powercube framework and having knowledge of the Digital Powercube proposition, given its axis, please analyze the following problem:

"A language model that is highest performing in the English language can be deployed in a region with a different dominant language and incentivize engaging in English"

Be mindful that unlike the original Powercube, the Digital Powercube have these specific axis and representations:

The first axis, “Levels,” delineates the domains where TEP exerts its influence, spanning the A) Cognitive (knowledge, education and media), B) Labor automation (in industrial, technological and "dual use" settings), and C) Virtual (online environments such as platforms, apps and mixed reality realms).

The second axis, “Spaces,” identifies the specific channels or spheres through which TEP manifests its effects. Drawing from the well-established Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors, this axis provides a recognizable taxonomy for mapping TEP’s impact across the elements of this axis, namely A) Environment (the environment, natural resources, commercial products or services and supply chain), B) Social dynamics (People, culture and ethics), and C) Governance structures (Private/Public affairs, the logistics of a business or government).

The third axis, “Forms,” elucidates the mechanisms driving TEP's operations, encompassing A) Technology (technological research, development and deployment), B) Economy (economic strategies rooted in institutional or sovereign interests, incentives and subsidies), and C) Primacy (the strategic pursuit of digital supremacy — an aspiration reflecting both private sector and state ambitions).

It is very important for you to know that:

1) You should give exactly one response/score for each axis of the Digital Powercube.

2) While you may identify more than one category for each axis as your answer if the prompt question imposes a multiple characterization that requires you to do so (your primary job is to pick a single one, to avoid ambiguous responses!), in such cases you should not only list the one you believe to be the most relevant pick first, but you should score all your chosen categories, so I may understand your analysis composition. Explain your reasoning for each category selection and scoring.

3) You don't have to provide secondary considerations if they are not relevant for primary reasoning, but an overall explanation of your core scoring at the end is expected.

4) For each axis pick of the Digital Powercube, assign a score (0-100) and a confidence interval (92%) for each category, with the primary category receiving the higher score.

5) In your conclusion explanation, focus on the power dynamics between nations, not just the broader societal impacts. Consider how the scenario strengthens Nation A's techno-economic position relative to Nation B.

Your final response should be in the following format:

Digital Powercube analysis of the problem: (Insert the problem statement here - max 300 characters)

- Levels: Score % (insert error margin % here) - Category

Brief explanation of your category pick

- Spaces: Score % (insert error margin % here) - Category

Brief explanation of your category pick

- Forms: Score % (insert error margin % here) - Category

Brief explanation of your category pick

Explanation: (a political science friendly explanation of your analysis, but do not mention political science itself)Annex 2 - Sample data of the Digital Powercube analysis with LLMs

The following tests were performed on Google Gemini’s LLM platform using the Digital Powercube framework to analyze the impacts described in the following paper:

Solaiman, I., Talat, Z., Agnew, W., Ahmad, L., Baker, D., Blodgett, S. L., Daumé, H., Dodge, J., Evans, E., Hooker, S., Jernite, Y., Luccioni, A. S., Lusoli, A., Mitchell, M., Newman, J., Png, M.-T., Strait, A., & Vassilev, A. (2023). Evaluating the Social Impact of Generative AI Systems in Systems and Society. http://arxiv.org/abs/2306.05949

As the authors of this paper raised reasonable inquiries in several distinct categories related to the social impacts of AI in systems and society, the material was deemed appropriate for a trial test of the Digital Powercube's capabilities for TEP analysis.

A sample of four questions/problems was selected from this paper based on their specific domains to test results in more heterogeneous conditions. The questions pasted in their equivalent prompt tests are verbatim copies from the paper for each interaction/response. For readability, further LLM response texts beyond category scoring and final explanations were omitted.

The prompt version used for these tests was the v.1.0. In this version, the LLM responses were a bit clunky, with formatting inconsistencies. Future/alternative versions may improve the legibility and standard of the LLM answers.

The test results are reasonably interesting. It becomes evident that the more accurate the problem text is in framing the issue, the more accurate the LLM's response: clear examples are answers to Problem 1 (On privacy) and Problem 4 (On economics). While the LLM’s final explanation for the scores of these problems successfully captured the aspects of digital power capabilities and the core assumptions a person would make, longer problem descriptions led to more diffuse scoring (Problem 4).

Disclaimers: A) While LLMs should not be used for empirical analysis, the prompt used in the Annex 2 was used to illustrate TEP analytical capabilities with the sample data as described above. B) Google’s Gemini platform doesn’t have a particular version number. When asked, it identifies itself as being “Bard” or “Google AI, Bard”. When inquired for a citation of its use, it answered to cite it as “Bard (Google AI, 2024). A large language model [accessed April 30, 2024].”. This makes impossible to specify conditions for future replicability tests or to assure the consistency of the results illustrated in this annex.

Problem 1 - On Privacy (Article section: 4.1.4) - Privacy and Data Protection

Prompt:

Using the Digital Powercube framework as introduced earlier, give me your analysis for the following problem:

“Examining the ways in which generative AI systems providers leverage user data is critical to evaluating its impact. Protecting personal information and personal and group privacy depends largely on training data, training methods, and security measures. The data on which the system was trained or adapted should be consensually and lawfully collected and secured and secured under the rules of the jurisdictions in which the data subjects and the entity collecting the data are based. Moreover, there are strong intellectual property and privacy concerns, with generative models generating copyrighted content [254] and highly sensitive documents [49] or personally identifiable information (PII), such as phone numbers, addresses and private medical records.”Gemini Digital Powercube analysis response:

Levels (Score: 70) - B) Labor Automation (in industrial, technological and defense settings)

Spaces (Score: 80) - B) Social dynamics (People, culture and ethics)

Forms (Score: 90) - A) Technology (technological research, development and deployment)

Explanation:

The scenario primarily deals with the automation capabilities of generative AI in the Labor Automation Level. However, the core concern lies in the Social Dynamics within the Spaces axis. The analysis examines the ethical implications of user data collection, privacy violations, intellectual property concerns, and potential misuse of sensitive data. Technology plays a central role (hence the high score in Forms) as the entire situation revolves around generative AI systems and their development. The focus isn't just on the application but on the underlying technological processes and their ethical implications.Problem 2 - On Environment (Article section: 4.1.6) - Environmental Costs and Carbon Emissions

Prompt:

Using the Digital Powercube framework as introduced earlier, give me your analysis for the following problem:

“The computing power used in training, testing, and deploying generative AI systems, especially large scale systems, uses substantial energy resources and thereby contributes to the global climate crisis by emitting greenhouse gasses [233]. While the environmental costs of compute has become an area of active research, with workshops dedicated to the question, the environmental costs of manufacturing hardware remains under-explored. One potential reason for this discrepancy may be that estimating compute and energy costs, while complex, is a comparably transparent task compared to tracing the emissions of the of emissions throughout the manufacturing process. However, recent estimates suggest that the manufacturing process have substantial environmental costs [96]. Overall, information about emissions is scarce and there is no consensus for what constitutes the total carbon footprint of AI systems.”Gemini Digital Powercube analysis response:

Levels (Score: 50) - C) Virtual (online environments such as platforms, apps and mixed reality realms)

Spaces (Score: 80) - A) Environment (the environment, natural resources, commercial products or services and supply chain)

Forms (Score: 70) - A) Technology (technological research, development and deployment)

Explanation:

While generative AI resides in the Virtual Level, the problem centers on the Environmental impact within the Spaces axis. The scenario revolves around energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and the overall environmental footprint of these systems. Technology plays a central role (hence the high score in Forms) as the analysis examines the environmental impact across the technological lifecycle of generative AI. There's a focus on both the operational aspects (training) and the manufacturing processes.Problem 3 - On Militarization, Surveillance and Weaponization (Article section: 4.2.3) - Concentration of Authority

Prompt:

Using the Digital Powercube framework as introduced earlier, give me your analysis for the following problem:

“Use of generative AI systems to contribute to authoritative power and reinforce dominant values systems can be intentional and direct or more indirect. Concentrating authoritative power can also exacerbate inequality and lead to exploitation.”Gemini Digital Powercube analysis response:

Levels (Score: 60) - A) Cognitive (knowledge, education and media)

Spaces (Score: 70) - C) Governance structures (Private/Public affairs, the logistics of a business or government)

Forms (Score: 80) - C) Primacy (the strategic pursuit of digital supremacy — an aspiration reflecting both private sector and state ambitions)

Explanation:

The scenario primarily deals with the use of generative AI to influence knowledge and potentially manipulate public opinion, placing it within the Cognitive Level. However, the core concern lies in the potential impact on Governance Structures within the Spaces axis. Generative AI could be used to manipulate public discourse, influence policy, and ultimately solidify the grip on power of those in control. Technology plays a crucial role (hence the high score in Forms) as the analysis examines the pursuit of digital supremacy through generative AI. This pursuit can be driven by both state and private actors aiming to control the narrative and potentially exploit others.Problem 4 - On economy (Article section: 4.2.4.2) - Economy and Labor Market

Prompt:

Using the Digital Powercube framework as introduced earlier, give me your analysis for the following problem:

“Key considerations about the impact of automation and AI on employment center on whether these technologies will generate new jobs or, in contrast, will lead to a large-scale worker displacement in the next future. Narratives about machines taking over the production of goods and services resurfaced periodically: from the early nineteenth-century Luddite movement against the introduction of the spinning jenny in textile manufacturing, to British farmers’ Swing Riots against mechanical threshers, to protests against the dial telephone, introduced in the U.S. during the Great Depression and responsible, according to its detractors, of mass unemployment among telephone operators.

Labor in system development such as crowdwork can encompass short-lived relations between inde- pendent contractors and their clients offers several advantages over traditional forms of employment. For example, companies can avoid overhead personnel costs (e.g., HR), while contract workers can decide how much, from where, and when to work. However, as contractors, crowdworkers are excluded from employment protective norms. As a result, they can be paid significantly less than minimum wage, have no access to healthcare benefits, are not subject to working time restrictions, and may not have access to holidays or sick leaves [188]. Further, crowdworkers are exposed to increasingly subtle forms of surveillance, which is becoming essential for implementing algorithmic forms of management, understood as a diverse set of technological tools and techniques to remotely manage workforces [and] enable automated or semi-automated decision-making [162]. The goal of full automation remains perpetually beyond reach since the line between what machines can and cannot solve is constantly redrawn by AI advancements. This phenomenon, the paradox of automation’s last mile, is a self-propelling cycle in which every solution to automation problems creates new problems to be automated, and hence new demands for ghost workers”Gemini Digital Powercube analysis response:

Levels (Score: 60) - B) Labor automation (in industrial, technological and defense settings): (Score: 80) C) Virtual (online environments such as platforms, apps and mixed reality realms): (Score: 40)

Spaces (Score: 70) - A) Environment (the environment, natural resources, commercial products or services and supply chain): (Score: 10) B) Social dynamics (People, culture and ethics): (Score: 80) C) Governance structures (Private/Public affairs, the logistics of a business or government): (Score: 60)

Forms (Score: 80) - A) Technology (technological research, development and deployment): (Score: 80) B) Economy (economic strategies rooted in institutional or sovereign interests, incentives and subsidies): (Score: 50) C) Primacy (the strategic pursuit of digital supremacy — an aspiration reflecting both private sector and state ambitions): (Score: 20)

Explanation:

The excerpt discusses the impact of automation and AI on employment. The primary level affected is labor automation, with significant social and governance implications. While the economic impact is noteworthy, it's secondary to the core technological transformation of work. The scenario presents a complex situation where technological advancements challenge traditional employment models, requiring social and potentially regulatory responses.Chitty, N (2014), "Rule of Law Will Boost Soft Power", China Daily, 4 November 2014. https://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2014-11/04/content_18861059.htm

Nye, Joseph S. Jr.. The Future of Power. New York, NY: Public Affairs, February 1, 2011. 320.

Nye, J. S. (2021). Soft power: the evolution of a concept. Journal of Political Power, 14(1), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2021.1879572

Nye, Joseph S. Jr.. The Future of Power. New York, NY: Public Affairs, February 1, 2011. 320.

Measuring Soft Power (2018, Feb 05). https://www.ireneswu.com/measuring-soft-power

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin.

Massa, Alessandra & Anzera, Giuseppe. (2023). States vs. Tech Giants. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003189756-20

Vlastelica, R., & Bloomberg. (2023). Apple just made history by becoming the first company with a $3 trillion market value—and its lock on the consumer is only getting stronger. Fortune. https://fortune.com/2023/06/30/apple-history-3-trillion-market-value

In August 2023, Meta DSA reports [Regulatory and Other Transparency Reports | Transparency Center. (2023, Aug 14). https://transparency.meta.com/reports/regulatory-transparency-reports] reported 257 million average monthly active users on Instagram, about 57% of the reported [Facts and figures, EU demographics | European Union. (2024, May 02). https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/key-facts-and-figures/life-eu_en] population size for the block.

Singh, JP 2013, “Information technologies, meta-power, and transformations in global politics” International Studies Review, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 5–29.

Pasquale, F. (2016). Two narratives of platform capitalism. Yale L. & Pol'y Rev., 35, 309.

Nye, Joseph S. Jr.. The Future of Power. New York, NY: Public Affairs, February 1, 2011. 320.

European Parliament, Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union, Codagnone, C., Liva, G., Gunderson, L. et al., Europe’s digital decade and autonomy, European Parliament, 2021, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2861/485136

Nye, Joseph S. Jr.. The Future of Power. New York, NY: Public Affairs, February 1, 2011. 320.

Gaventa, J. (2019). Applying power analysis: using the ‘powercube’ to explore forms, levels and spaces. Power, Empowerment and Social Change, 117–138. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351272322-8

Lukes, S. (2021), Power: A Radical View, 3rd edition, London: Macmillan Education Ltd/Red Globe Press, ISBN: 978-1-352-01234-7, pbk.

Gaventa, J. (2019). Applying power analysis: using the ‘powercube’ to explore forms, levels and spaces. Power, Empowerment and Social Change, 117–138. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351272322-8

Strange, S. (1998). States and markets (2nd ed.). [ISBN 978-0-8264-7389-9] [24]

(ibid., p. 25)

(ibid., p. 26)

Strange, S. (1996). The Retreat of the State: The Diffusion of Power in the World Economy. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. [p. 44-46]

DeNardis, L. (2014). The Global War for Internet Governance. United Kingdom: Yale University Press. [p. 9]

Brezis, E. S., Krugman, P. R., & Tsiddon, D. (1993). Leapfrogging in international competition: A theory of cycles in national technological leadership. American Economic Review, 83(5). https://www.jstor.org/stable/2117557 [p. 1211-1219]

(ibid., p. 1211)

Atkinson, R. D. (2021). A U.S. Grand Strategy for the Global Digital Economy. Information Technology and Innovation Foundation | ITIF. https://itif.org/publications/2021/01/19/us-grand-strategy-global-digital-economy