The Rise and Fall of [AI powered] Nations

Why choosing algorithmic pluralism instead of the false dichotomy between democratic values and technocratic efficiency is the answer to catastrophic thinking

Preface

This article is part 2 of a series titled: Post-Human Politics: An Algo-Intelligentsia Political Theory. In it, I explore political concepts and frameworks to establish new directions for statecraft and nation-building in the algorithmic age. Part 1 is available here. In this installment, I propose a Fourth Branch of government as model for AI governance, combining constitutional theory and institutional design in a bold new manner. Not only that, the governance structure of the branch itself is designed to be a novel approach, ready for today’s and tomorrow’s AI agents.

With no intention to be definitive nor authoritative, the proposal in this article offers a meaningful contribution and ideas that can improve civic engagement with AI, and facilitate cooperative AI geopolitics even between adversarial states, without requiring ideological alignment. Drawing inspiration from historical examples of constitutional innovation, it embraces the political resistance, knowing well that the path for constitutional amendment is extraordinarily difficult, and that Congress, the President, and courts are bound to resist ceding authority to a new constitutional entity. Nevertheless, the present material provides a foundation for this reasoning and effort, conceiving optimal efficacy of the engines of state as paramount for the challenges of tomorrow, where the speed of AI far exceeds the speed of political cycles and legal deliberation of our most readily available instruments for AI governance and regulation. A sample constitutional amendment is included in Appendix A, Appendix B presents simulated case studies that illustrate how the concepts explored in this article could effectively respond to real-world governance challenges, and Appendix C proposes an initial audit model for the proposed 4th branch, the AIGB.

A Timely Bifurcation

Nations today stand at a defining juncture regarding AI:

Should it be absorbed as a foundational element of statecraft, or merely as an auxiliary tool—much like digitization was largely perceived?

Should governments retrofit AI into existing institutional frameworks, or is the moment ripe for a fundamental redesign of state architecture?

In administrative settings, both these questions press against a deeper tension: What if incremental legal adaptations have reached their limit? How far can ad hoc and ex post policy-making truly carry us? Will our governments recognize they crossed the Rubicon, from which the engines of the state must be upgraded, not simply updated?

In politics, updates are relatively straightforward: with sufficient support, policies move forward; without it, issues are deferred to the next election cycle, hardly rocket science. Upgrades, however, demand political and institutional will, vision and sustained execution, rarely seen qualities in modern governments.

True upgrades require monumental efforts, likely exceeding a single presidential term. And bureaucracies, built for stability not transformation, are ruled by budgetary constraints that often reinforce inertia, which ultimately hinders significant changes. Ordinary political resources that once enabled monumental commitments toward monumental undertakings got lost along the way: We no longer build pyramids or raise monuments to Liberty or Justice, but we have great apps!

So, if AI is to be seen as foundational, demanding a structural upgrade of the very engines of the state, how should we grow intelligently rather than reactively?

The UAE Approach on AI Governance

In 2017 the United Arab Emirates innovated more than of any other nation on Earth: they appointed Omar Sultan Al Olama as Minister of State for Artificial Intelligence, a bold move that positioned the UAE as thought leader in AI policy, enabling it to punch above its weight diplomatically and to establish a unified and forward-looking national AI strategy. And more than a statement of ambition, they set a governance precedent: today several countries have followed suit and have similar positions, agencies and roles.

Having a dedicated focal point for everything AI enables sharp political coordination, fosters cohesive national programs and allows long-term strategies to take shape and form, no doubt highly relevant imperatives for a transformative general-purpose technology like AI.

Even so, the matter of algorithmic governance and effective regulation is still a foundational objective for UAE’s “National Strategy for AI 2031”. Which begs the question: what does 2031 AI looks like for nations and governments?

Despite mounting geopolitical pressures over the logistics of equipment and talent involved in AI development, it is increasingly likely that the 2030s will bring us closer to achieving AGI or ASI capabilities. Hypotheticals aside, imagining better, cheaper and more effective AI is a rather realistic anticipation, where we can expect the proliferation of not one, but multiple “super AI” platforms available globally. And equally important is the shifting perception of AI systems—not as off-the-shelf software, but as national security assets, subject to robust procurement, development, and deployment frameworks historically reserved for dual-use technologies.

Consequently, nations best positioned to anticipate and deploy structural reforms over the coming five years are unequivocally best positioned to effectively integrate and harness tomorrow’s AI capabilities. However, the most significant setbacks to executing these forward-looking strategies are often internal: institutional inertia, bureaucratic lag, misused funds and siloed governance competition. To overcome this, nations must engineer a form of political escape velocity, a decisive reconfiguration of governance, not just a symbolic adjustment. And while appointing a minister for AI is certainly beneficial in many fronts, the challenge now is to identify and deploy true institutional accelerators. At surface level, what are some essential catalysts?

On the Competence and Strategy of Successful AI Nations

As starting point, it is perhaps wise to assess which nations demonstrate a consistent capacity to build consensus around strategic initiatives:

The ranking above lists the top 15 nations for consensus-building in policy development, using the SGI (OECD + EU countries) and BTI (developing countries) indexes. The numbers highlight an empirical notion of Knightian uncertainty—where outcomes can be anticipated, but no probabilities can be asserted—as preparedness involves the capability for both political and economic coordination. However, as AI is relatively affordable to make and increasingly accessible to buy, the real challenge lies in evaluating the strategic weight of these options from a sovereign perspective. Three paths exist:

The table above (download its data for a detailed rationale for each item) outlines strategic pros and cons for GovAI initiatives, peculiarly, from the perspectives of procurement and internal capacity. While political will and financial resources shape feasibility, the table makes clear that each approach raises distinct challenges that might be mitigated with legal or institutional mechanisms, although, with broader implications for sovereignty and long-term national aspirations. Importantly, these are not deliverables of a single administration; they are inherently cross-administrative and trans-electoral in nature—requiring sustained consensus-building. From a realistic perspective, addressing these choices demand a renewed perspective: One that asserts true patriotism over short-term clientelism and political stalemates.

Therefore, integrating this powerful resource, with its profound implications, compels governments towards an unprecedented level of governmental self-scrutiny, here powerfully articulated by Engstrom, who suggests that AI might ultimately force a more rigorous examination of all governmental operations:

The alternative, of course, is to apply greater scrutiny to all government action, not just the algorithmic sort—a levelling up of regulatory stringency across the board. Even before AI, one could argue, government was plenty secret, regressive, racist, myopic, relentless, and repressive. Why not subject all government operations to more scrutiny? AI might thereby hold up a mirror to our democratic system and force us to do better.

What we choose to automate, how we achieve it, and how we transition to and assess these new tools all raise questions about the very identity of the state, lasting changes that define our nations’ shape and form for many years to come.

Thus, the question over how resilient a state is regarding oversight and deployment of today and tomorrow AI resources emerges: Do we need an FDA for AI? An AI ministry? How to legislate over unknown applications and avoid over-regulation at the same time? Can patched legal adaptations secure us a coherent framework for an increasingly intelligentized state without merely automating inefficiency?

Liberal constitutionalism entails a commitment to maintaining bounds on state power. That commitment is tested when "the technological and military character of governments and the productive relationships" of society change. The "powerful and highly generalizable" technology of machine learning poses a challenge to our constitutional system because it has the capability to transform the relationship between the state and its citizens.

Huq, Aziz., Constitutional Rights in the Machine-Learning State, (2020)

Ultimately, I am inclined to ask: Can we confidently trust that the three branches of power, vastly invested in partisan and power divisions are enough to not only deliver the changes needed for this moment, but to also preserve constitutional democracy in face of an increasingly algorithmic state machinery that touches all we see and do?

While many may answer “no” to this question, the issue is how to innovate upwards, beyond our inherited blueprints. My argument is that the tripartite Montesqueian schemata of the three branches of government was never designed for an automated world, and left to this [now] archaic construct, today’s political arrangements are set to sleepwalk into reinforcing market imperatives that over the past twenty years have grown increasingly hostile to the interests of the very object democracies were designed to protect: the people.

On Non-Harmonized AI Governance Arrangements

But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

James Madison - The Federalist Papers no.51

In the quote above, Madison discusses the importance of checks and balances and the separation of powers in the U.S. constitution, and in bold, the object of our analysis: If the future of public governance is to become a hybrid of AI and men, how should we engineer this ensemble to prevent the automation of tyranny, corruption and other systemic flaws so inherently ingrained in our political dynamics?

Ministries—whether infused with both executive and legislative functions as in the U.K., drawn from the legislature to serve the executive as in Brazil, or strictly appointed by the executive, as with secretaries in the U.S.—are institutional arrangements ultimately accountable to the head of government. Such executive authority, in turn, is shaped by term-limited politics and partisan dynamics, often becoming path dependent on the politics and lobbying forces that influenced their ascent to power. Put another way, while in the UAE the tenure of the AI minister is at the discretion of the President and the Prime Minister, both of whom are hereditary monarchs rather than elected officials—a set-up that enables long-term strategy and deliverables to stand out—in other nations, any such figure would likely be constrained by electoral cycle priorities and executive turnover.

Another emerging lesson is that simply replicating past institutional strategies in the AI era is inefficient. We already observe what could be termed “Montesquiean aberrations”: functional extensions of state power that neither constitute new branches nor fit squarely within existing ones—we call these “agencies”. Though not formally embedded in the constitutional architecture, agencies exercise real authority, being quasi-legislative, quasi-judicial or quasi-executive, with varying degrees of independence. The Federal Reserve, FCC, SEC, CIA in the U.S. or the MP, TCU and Banco Central in Brazil all enjoy relevant independence, orbiting the three branches as some form of “constitutional satellites” whose effectiveness often coming from limited political insulation, shielding their autonomy at surface level.

Still, calls for governance models respond for legitimate anxieties, with AI task forces, commissions, licensing schemes, and risk assessment frameworks taking the front-line of careful legal adaptation. However, actors in this arena are complex entities and often sport sufficient political mass to entertain troubling geopolitical ambivalence facing these endeavors. One example is OpenAI’s Sam Altman, who once called for a new agency to license AI, addressing political concerns through safety standards. Yet, he also threatened to cease EU operations if regulatory burdens ever become too onerous. Blackmail or not, it seems to have worked.

And while an “FDA for AI” might feel as a reasonable compromise—especially in managing narrow AI risks—such equivalence falls short, as AI systems are hardly a single product: its risks are diffuse, actors are decentralized, and its development is continuous. FDA-like rules presume measurable risks, observable actions, and enforceable constraints—none of which are realistic for today’s AI, and likely won’t be for tomorrow’s AI either.

In 2025, beyond voluntary commitments, AI regulation is broadly tied to two models: a bottom-up patchwork quilt of executive orders, norms, policies, and guidelines, or top-down legal frameworks, such as the EU AI Act—comprehensive in scope but subject to institutional limitations. And China, who also regulates many aspects of AI through existing power structures (e.g., China’s Cyberspace Administration office), is also susceptible to political interference, much like their geopolitical counterparts.

In common, these efforts share key weaknesses: lack of international interoperability, weak specificity, questionable proportionality, and limited enforcement capacity. Moreover, they are born into existing—often understaffed, underresourced—agencies.

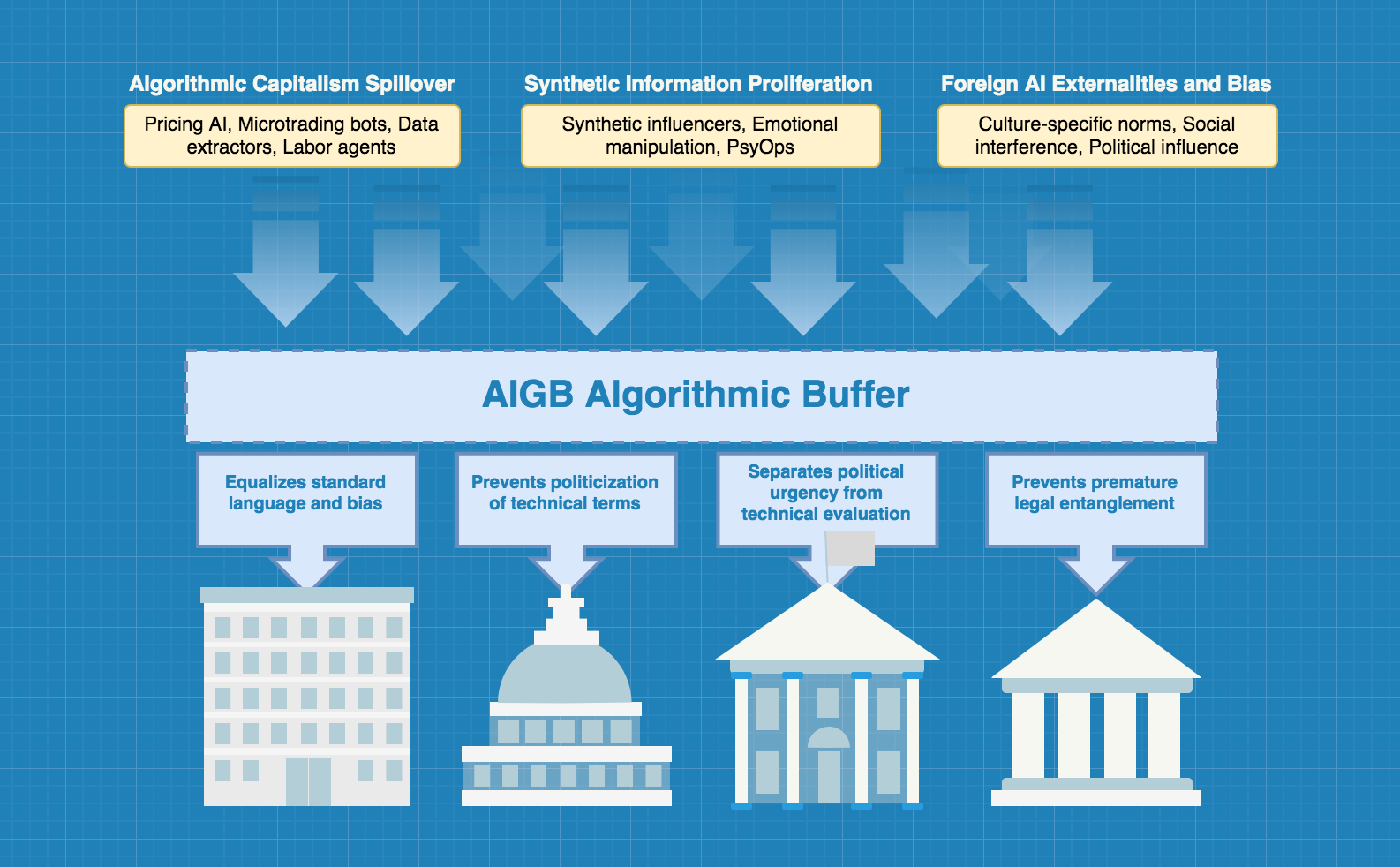

De facto, this results in soft, non-harmonized regulatory standards for AI, where extreme cases of algorithmic harm are litigated case by case, rather than systematically legislated. Telecommunication standards enable global connectivity without requiring political unity, Central Banks coordinate monerary policy between distinct political settings, so how should AI governance build (and enforce) standards?

Polymorphic by design and increasingly more robust as months go by, AI systems of every kind are expected to conform to legal frameworks shaped for industrial-era risks, regulated not by legislative overhauls but by interpretive adaptation, perpetually vulnerable to economic and political capture.

If AI to join humans in the machinery of governance, it must also be subjected to institutional controls—not merely as a technical system, but as a political actor embedded in human decision-making. The challenge lies in overcoming bureaucratic vices and organizational bottlenecks, to prevent the large-scale automation of bad practices, the creation of new loopholes, and the rise of “smart corruption”.

Towards a Federated Fourth Branch for AI

I propose a new constitutional model—not a bureaucracy, but a protocol: A federated fourth branch of government, designed as the immune system of sovereign AI governance. This is not merely another agency, task force, or regulatory patch, but a foundational layer purpose-built to interface with and govern the complexities of present and future AI systems. Rather than confronting existing powers, it streamlines and absorbs AI’s initial shockwave to normalize its administrative, legal and participatory diffusion across traditional institutions and instruments of governance.

Rooted in adversarial interoperability, this model is architected with geopolitical realism at its core. It features a domestic constitutional unit with international interoperability—a structural analogue to how national central banks relate to the IMF—serving as the national implementation node of a broader international AI accord, thus enabling a networked architecture for common governance while preserving national sovereignty. Such arrangement rationalizes and absorbs the diffuse Ostromian polycentricity currently tasked with regulating, standardizing, and interfacing with AI capabilities, a competence that might be presciently adequate.

We live in a world where any actor—adversarial or allied—may eventually develop unconstrained systems, AGI or ASI outside any alignment regime, oversight body, or responsible framework, it becomes clear that global AI alignment is the floor, not the ceiling. The proposed fourth branch would offer a scalable domestic architecture, designed to enforce civilizational guardrails even amidst geo-political fragmentation.

Constitutional innovation is rare. Most policy experts work within the constraints of existing frameworks, focused on retrofitting, regulating, or optimizing legacy systems, treating AI as a policy silo rather than a regime-shaping force. Moreover, the truth is that we are all trying to fix a plane mid-flight, but: Computer scientists lack statecraft experience; policy professionals have no intimacy with AI technical stakes; futurists underestimate institutional dynamics; and lawmakers can’t write a “Hello World” in Python. So this proposal bridges geopolitical realism, AI and political engineering, hopefully establishing a path so that all these stakeholders see constitutions not as holy relics, but as nation-building tools, and dare to play with constitutional design.

If we are to move beyond technical regulation and philosophical reflection—such as those vented by soft-power coordination platforms as the OECD or WEF—then we must ask: how should the institutional machinery of the state be reimagined for the AI age?

In other words: If we can and should upgrade the operating system of the state itself, where do we start?

If AI becomes infrastructural to civilization (like electricity or the internet), then AI governance becomes foundation to statecraft. Just as Alexander Hamilton helped architect the executive branch for industrial capitalism, perhaps it is time to redefine the state once again—for its algorithmic era.

The Case for an AI Governance Branch (AIGB)

As a constitutionally-anchored Fourth Branch, the AIGB offers what no agency or ministry can: Structural immunity from the very forces now distorting AI governance, namely elite capture, inter-agency turf wars, political short-termism, and the erosion of public trust. When AI oversight is fragmented across dozens of state-level initiatives or siloed within executive departments, it creates a governance patchwork that is vulnerable to inconsistency, loopholes, and lobbying. Worse, it exposes AI governance to political control, enabling the manipulation of regulatory agendas, fund throttling, and direct interference—precisely what we see unfolding today with agency gutting and corporate favoritism. The AIGB sidesteps these failure modes by occupying a co-equal constitutional status: presidents cannot dictate its mandate, suppress its findings, or capture its functions through appointments alone.

More than a coordinating node, the AIGB can become the sovereign steward of a unified, a nation-scale AI framework of norm-driven cooperation, consolidating oversight, enforcing interoperable standards, and eliminating duplicative data pipelines and regulatory confusion across subnational entities.

While Central Banks, intelligence agencies, to name a few, stretch the original state design without breaking the classic three branches model, a fourth branch is then a constitutional immune system, more prepared to evolve governance in lockstep with AI itself. Anything less—a fortified agency, a longer-term commission, a “FED for AI”—misreads the problem: this is not a management issue, the fourth branch is pure constitutionalism, and it expands the democratic arrangement for the safety and efficacy of the state. Ideally, a constitutional AIGB cannot be defunded, is harder to kill and harder to corrupt, and by anchoring it in the charter of the republic, we shield the long-term from the short-term. Form matters. Equality matters. Without co-equal status, AI governance will be pushed to the margins—undervaluated, underfunded, and possibly overrun by corporate actors. Formal elevation means real autonomy, real legitimacy, real teeth. In short, a fourth branch isn’t an ornament, it’s an institutional firewall between society, accelerated AI R&D, and regulatory capture.

Finally, in creating a new branch from scratch, we may engineer its operations without vices and operational heritage. So in the present proposal, the fourth branch is then a paperless, constitutionally protected, machine-speed capable AI arm of the state. And if we seriously understand that AI may soon be powerful enough to reshape economies, laws, the job market and public governance itself, then any model of AI governance must be able to match such pace, scope and intelligence.

Funding wise, the initial proposal is for the branch to set a “Kinetic Fee”, a 0.5% tax on high-volume AI computations (e.g., perhaps above a certain threshold, say 1 million operations). This aims to target high-impact AI users (e.g., corporations, governments) without burdening small players and R&D initiatives. Ideally, would work as a future-proof funding mechanism of its own—estimated at $1–2 billion annually—potentially freeing the branch from congressional budgets, safeguarding its independence.

However, to fully represent a new form of independent oversight, the AIGB requires a custom-built model of governance too.

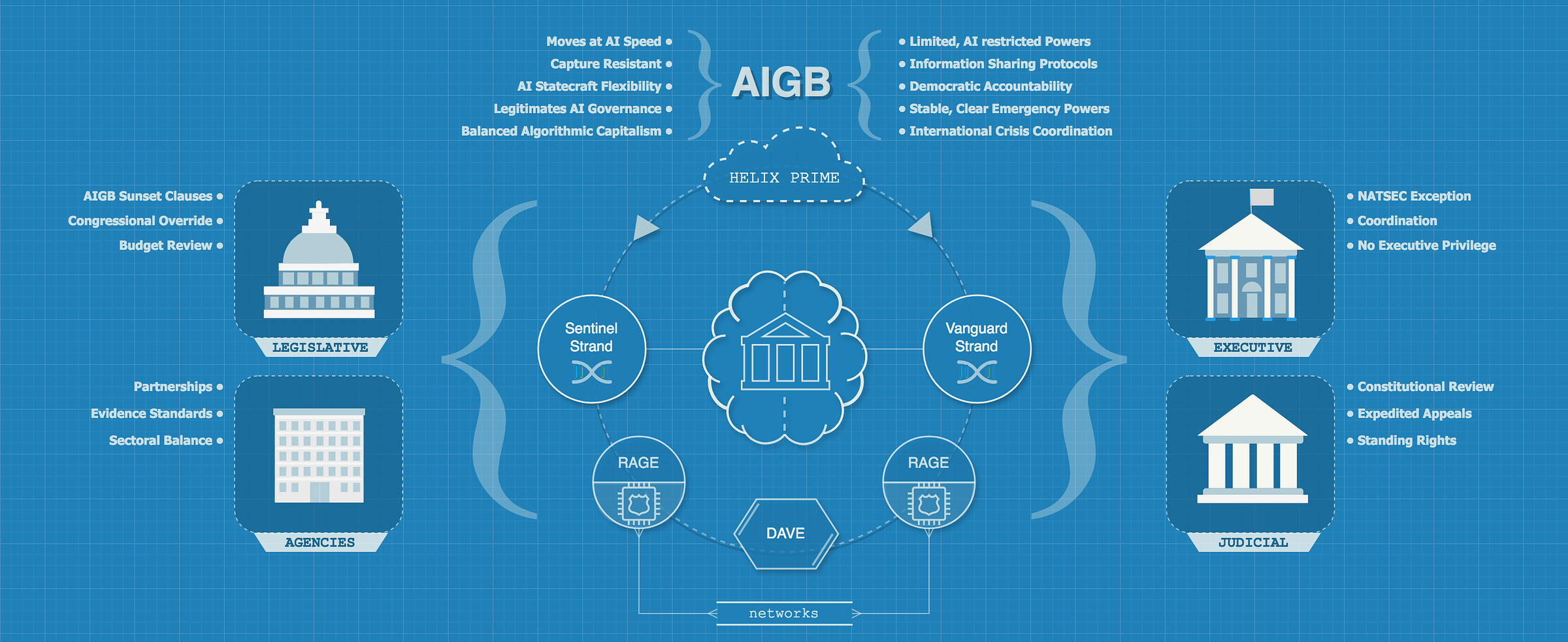

The Helix-RAGE Governance System (HRGS)

AIGB’s proposed structure and operations are not only digital but also highly automated: The AIGB introduces a groundbreaking governance model, the Helix-RAGE Governance System (HRGS), blending two innovative frameworks: Helix, a human-centric, dual-strand structure, and RAGE, a distributed, AI-augmented network of cognitive modules or agents. Together, they create a robust, adaptive system designed to regulate today’s AI and seamlessly govern any future AGI/ASI, ensuring long-term safety, innovation, and democratic alignment.

✦ HELIX: A Dual-Strand Framework

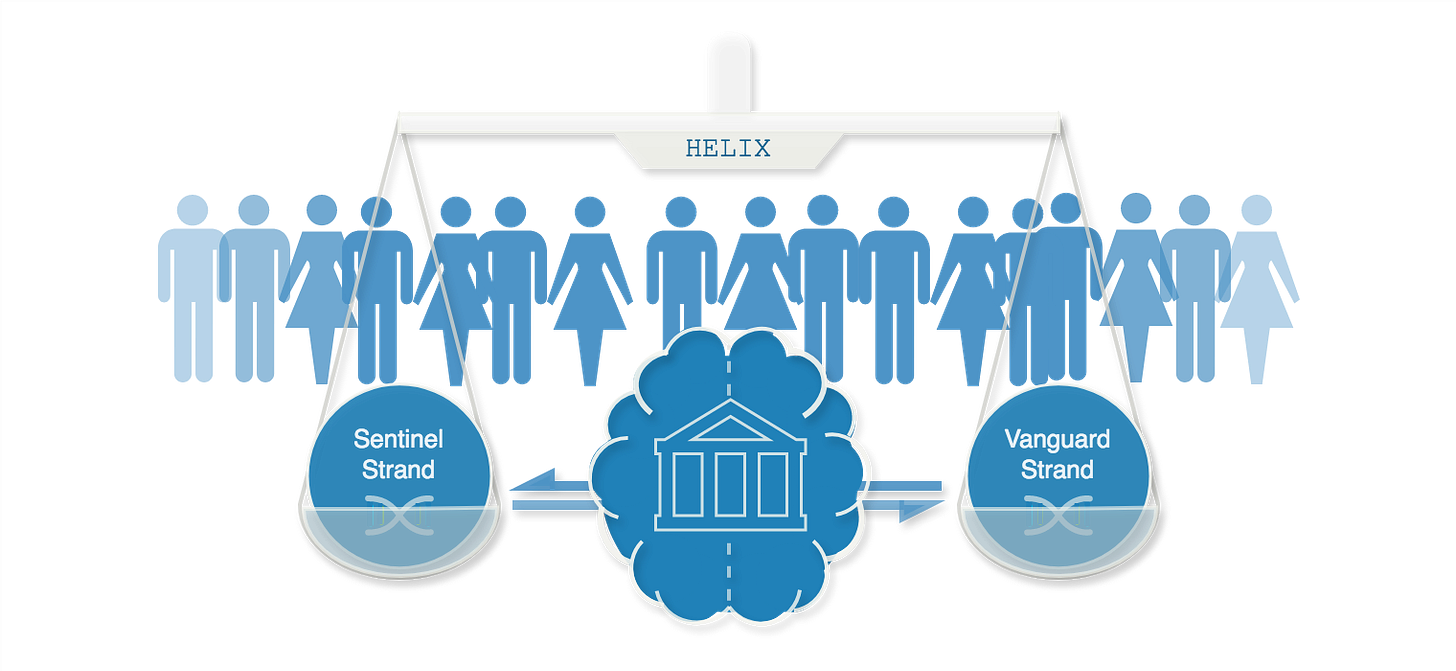

HELIX is a self-regulatory system that operates like a double-helix structure—two intertwined strands of authority that dynamically balance each other. One strand, called Sentinel, focus on regulation and oversight, the other, the Vanguard Strand, on innovation and integration, ensuring both control and good use of AI technologies. It’s adaptive, lean and it keeps human oversight firmly in the drivers seat.

The strands operate in a symbiotic tension: Sentinels can veto Vanguard proposals that risk safety or ethics, while Vanguards can challenge Sentinel regulations that stifle progress. Major decisions (e.g., AGI deployment) require a 70% consensus across both strands, ensuring collaboration without dominance. Unlike traditional hierarchies, strands are forced to collaborate, fostering adaptability and resilience.

In this initial design, Helix proposes a Pulse Algorithm governance model that randomly replaces 25% of each strand (13 members) every X months, assessing performance and public feedback. Candidates, drawn from a global pool, undergo rigorous AI-driven integrity scans, barring political or corporate influence. This rolling renewal, coupled with transparent vetting, should work as yet another layer capable of further shielding Helix and the AIGB from lobbying and corruption.

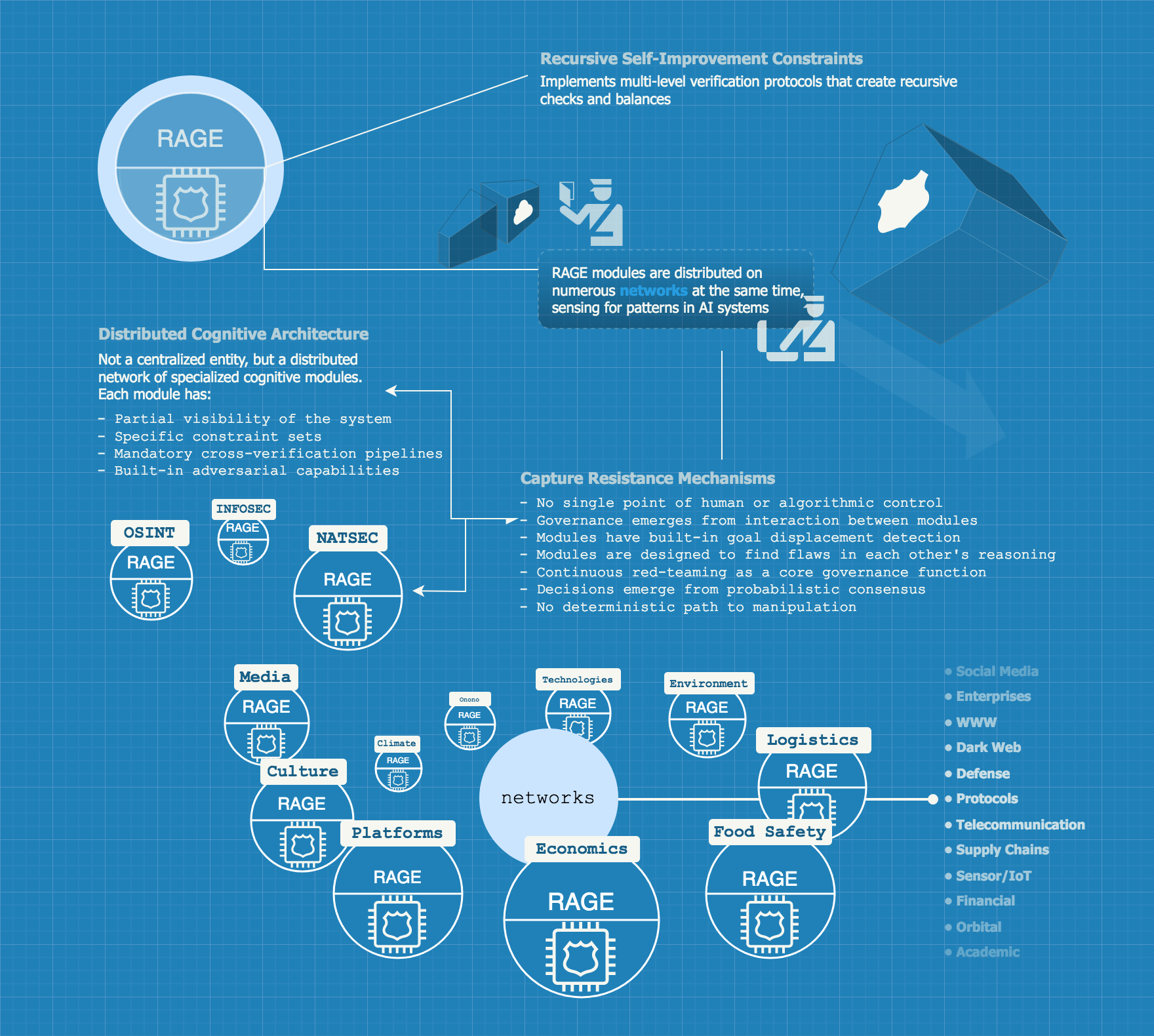

✦ The Recursive Autonomous Governance Engine (RAGE)

RAGE complements Helix with a technical, distributed network of competing cognitive modules, each embodying a unique and specialized governance paradigm. Unlike centralized and monolithic systems, RAGE modules have partial system visibility and built-in adversarial testing, designed to detect flaws in: Each other’s reasoning, Helix voting patterns, and the broader AIGB framework. Governance emerges from their interactions, grounded in immutable ethical and constitutional constraints.

Inspired by Autopoiesis theory, RAGE treats AI—including potential AGI/ASI—as integral to its ecosystem, acting as both participant and subject of governance. Configured as actors and observers in Helix operations, RAGE modules introduce controlled noise and certification weight, enhancing decision robustness while preserving human independence. This quasi-living evolving layer resists capture, safeguards systemic values, and adapts to emerging technologies, serving as a guardian of the logic around human deliberation.

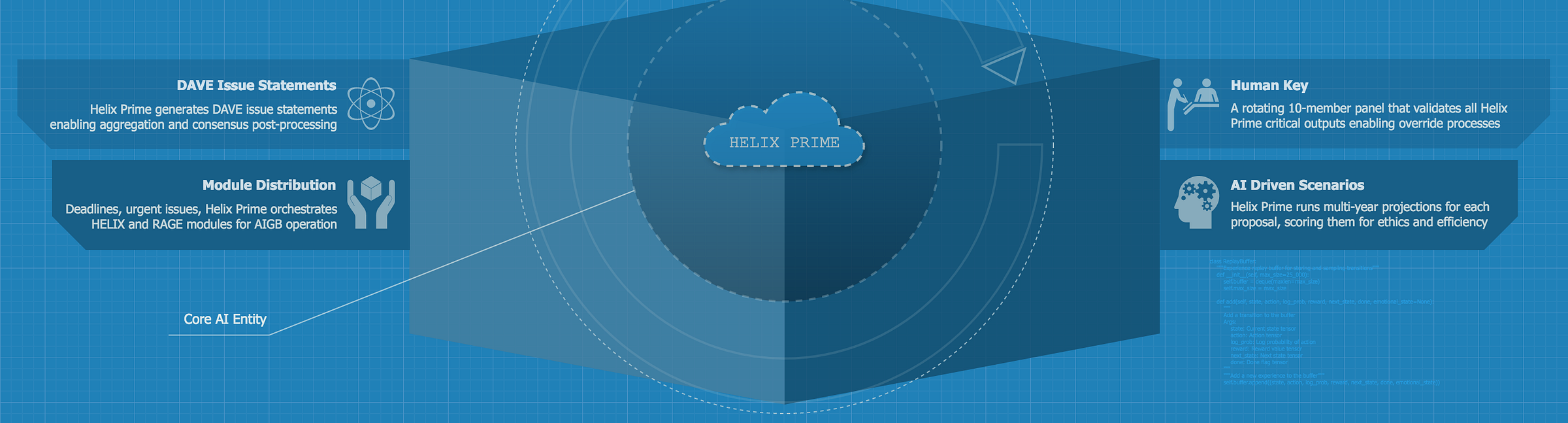

✦ Helix Prime: The AI Backbone

Thinking ahead to future AGI/ASI entities but ready for today’s AI, at the heart of the HRGS lies Helix Prime, AIGB’s operational core. Sandboxed to prevent autonomous overreach, Helix Prime powers DAVE’s vote fusion, data processing, complex regulatory/risk analyses, and simulated scenarios. Its Cognitive Firewall dynamically adapts to RAGE behaviors, enforcing constraints if misalignment is detected. And whenever facing critical decisions, Prime require unanimous approval from a rotating Human Oversight panel (five Sentinels, five Vanguards), ensuring human control.

Prime keeps nations ready for AI—eventually enabling the HRGS to absorb AGI/ASI’s power as a tool, not a threat. It views advanced AI’s as partners, locked under human command, and when tied with DAVE, Prime is a corruption nightmare: it is controlled chaos at the service of integrity, a model to all public services and the ultimate container for talent building within the government. Ultimately, Helix Prime is a constitutionally aligned model, measuring AIGB’s efficacy and ethics.

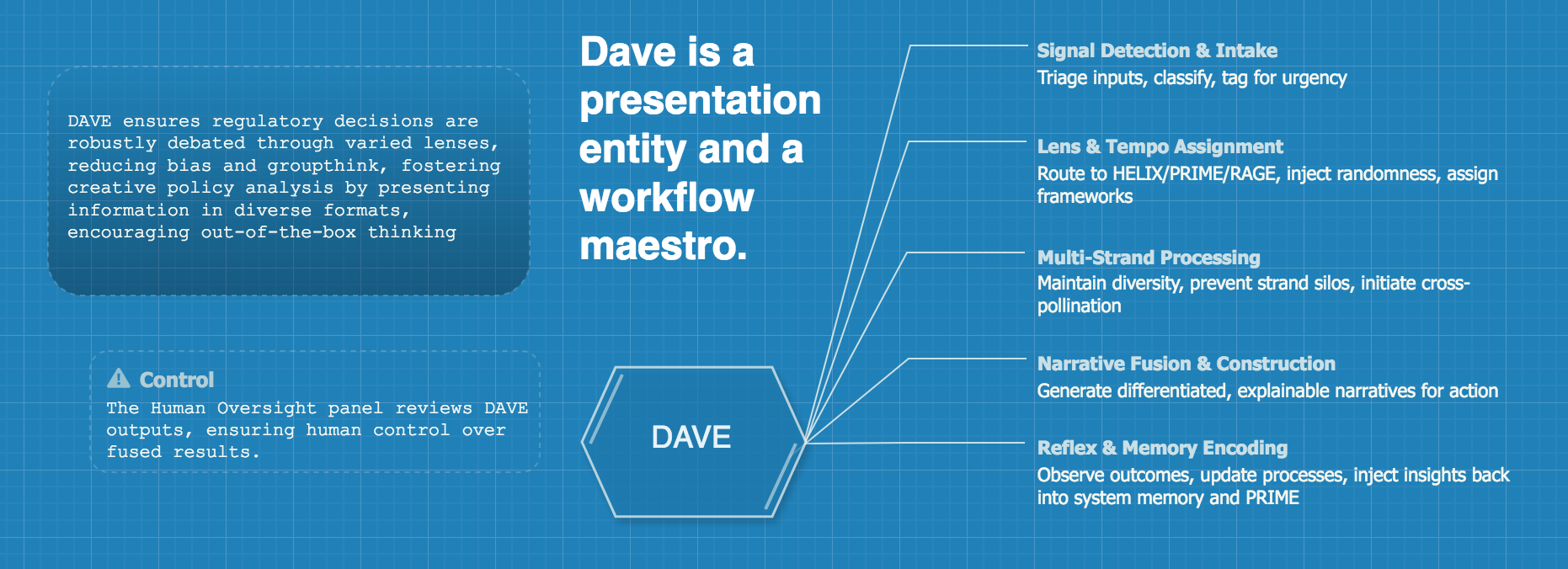

✦ Differential Asynchronous Voting Engine (DAVE)

DAVE revolutionizes decision-making within Helix, using AI to present issues uniquely and process votes asynchronously, thwarting collusion and corruption.

DAVE’s Probabilistic Consensus Algorithm aggregates these diverse inputs, normalizing formats and weighting votes by expertise, performance, and relevance. Probabilistic adjustments add unpredictability, preventing deterministic exploitation. Partial outcomes guide ongoing votes without revealing individual positions, culminating in a 70% cross-strand consensus for final decisions. By presenting issues uniquely and staggering votes, DAVE ensures decisions are robust, transparent, and resistant to external influence, reinforcing the AIGB’s integrity.

AIGB Governance at a Glance

Ultimately, the AIGB is a constitutional ecology. Like any living system, it adapts not by command, but by design—it co-evolves with the terrain it governs, rather than positioning itself above it. It is a post-jurisdictional branch: not a judge, not a ministry, not a court. Simply put, the AIGB doesn’t operate through ministries or boardrooms—it governs through architecture, not hierarchy. It is a living, adversarially coherent protocol that replaces fragile institutional pillars with a dual-strand cognitive system built for resilience, interpretability, and evolution.

In this model, priority-setting does not arise from static statutes or top-down ministerial decrees, but through the attention mechanics of HELIX and HELIX PRIME. The former engages in an ongoing dialectic between Sentinel and Vanguard strands, while the latter synthesizes feedback from purpose-built RAGE modules—each using context-specific analytical lenses such as PMESII-PT, PESTEL, or hybrid methods like a political Bradford Hill analysis. In specialized domains, learning models may invoke targeted instruments like the SALSA framework (Signals, Anticipation, Learning, Sense-making, Action).

Finally, the AIGB is not merely procedural—it functions more like a biocybernetic nervous system: reflexively fast through RAGE + DAVE diffusion, deliberative through HELIX PRIME, and ethically and cognitively modulated by Sentinel and Vanguard. It is a governance model not just for administering order, but for living in complexity—a constitutional architecture fit for the algorithmic age, more technically-driven rather than politically-negotiated. In being technically-driven, the AIGB provides a crucial function often missing in contemporary governance: it enables a clear distinction between what is technical and what is political. This structural clarity reduces the overreliance on ad hoc subject matter expertise by lawmakers and establishes a foundation where digital governance is rooted in rigorous, interpretable standards rather than transient political whims. Such an arrangement not only suits an increasingly automated world, but also allows for an unbiased and harmonized governance layer—one that can absorb the complexity of AI systems and cascade informed, context-aware guidance down to more traditional powers. In this way, it helps untangle the language of digital systems from real-world politics, offering a more resilient interface between constitutional order and algorithmic infrastructure. The AIGB may be ahead of its time, but given multiple and concurrent efforts from AI giants, it stands as a natural extension—ready to be honed and harnessed.

Engaging Stakeholders: Balancing Governmental Oversight and Public Voice in AIGB Governance

The Triad Liaison Council (TLC) serves as a bridge between the AIGB and the traditional branches of government, ensuring their perspectives inform AI governance without compromising the branch’s autonomy. Comprising six representatives—two each from the executive, legislative, and judicial branches—the TLC meets quarterly to offer non-binding recommendations on AI policies, which the AIGB considers during its annual Spiral Summit. The Legislature can also trigger formal AIGB policy reviews through a supermajority resolution, compelling it to assess specific decisions and publish outcomes transparently. Similarly, the Judiciary may challenge AIGB actions on constitutional grounds, receiving securely encrypted evidence to evaluate compliance; decisions are either upheld or revised, with all proceedings broadcast live.

On the public-facing side, the Citizen Echo Portal (CEP) empowers individuals to shape AI governance by submitting “Echoes”—short, verified inputs —which an AI aggregates into sentiment clusters. Should a cluster gain X million endorsements, the AIGB reviews its issue framing, broadcasting the process via the Echo Chamber, a live-streamed platform that ensures transparency across AIGB actions. Conceptually, debates, votes, analyses and deliberations, can be all streamed live via Echo Chamber in AIGB official channels. Solution wide, many platforms and initiatives already provide foundational elements for this level of digital participation.

The Chaos Shield, a rigorous security mechanism, employs ethical hackers and decoy decisions to stress-test the system, reporting vulnerabilities to the Complaint Resolution Protocol (CRP). The CRP analyzes feedback from the public, TLC, Legislature, and Judiciary, simulating fixes and proposing adjustments for integration during the Spiral Summit, with test summaries shared publicly via Echo Chamber. This dynamic interplay ensures the AIGB remains responsive and resilient, turning external input into strengths without succumbing to pressure.

Together, these mechanisms weave a robust model of accountability and adaptability. The TLC, Legislature, and Judiciary provide structured governmental input, while the CEP, Chaos Shield, CRP, and Echo Chamber foster public trust and systemic robustness. By channeling feedback through the Spiral Summit and maintaining strict boundaries on external influence, the AIGB listens attentively to stakeholders while safeguarding its mission to govern AI responsibly, ensuring a governance model as innovative as the technologies it oversees.

The Constitutional Protocol: AIGB as Immune System

The AIGB protocolized design allows it to be instantiated across nations, adapted to different legal and cultural contexts, but still capable of speaking a shared governance language. This is perhaps its key innovation: the AIGB is alignment infrastructure with state privileges, but modular enough to interlink internationally—like an API for institutional trust.

AIGB’s adversarial interoperability principle offers coordination incentives without calling for coercive enforcement, similar to how countries adopt Basel banking standards to maintain access to global financial systems. Nations that don’t adopt AIGB-like structures risk to become informationally isolated, losing access to shared threat intelligence, early warnings, coordinated response capabilities, to name a few.

This design allows a country to retain full sovereignty, but also plug into a trans-sovereign, decentralized early-warning and safety coordination system—capable of red teaming frontier models, flagging emergent AGI capabilities, and triaging crisis escalations, all without needing to politically align with Washington or Beijing. The AIGB is neither Western, Eastern, or non-aligned; it is pre-aligned to the existential stakes of advanced AI, enabling information sharing, risk assessments and crisis responses to be based on technical standards, using policy imitation and competitive benchmarking as governance tools that precede slower political response times.

The challenge lies in constitutionalizing the AIGB rather than merely codifying it in statute, so that nations inoculate it against political capture, budgetary sabotage, and partisan interference. It then becomes a foundational civic actor, not a fragile extension of today’s politics. This distinction—constitutional permanence vs. administrative convenience—is what makes this model not just robust, but vital.

AI cannot be supervised by yesterday’s machinery, and a self-sufficient fourth branch is more than fit for the task at hand. It is a forward looking resource, a first-principles institutional innovation that empowers diplomacy and sovereignty.

Discussion

While I once supported the idea of establishing supranational institutions to govern AI—via UN, an IAEA for AI, or a global AGI observatory—experience and historical patterns have tempered that optimism. Global institutions, while noble in principle, often suffer from structural weaknesses rooted in the political and economic will of their most powerful members. Funding volatility (as seen when the United States withheld or delayed contributions to the UN), geopolitical weaponization of participation, and lack of enforceability have all undermined their credibility. Even the International Court of Justice, ostensibly a global judicial body, faces glaring limitations: its rulings are not binding on all states, and it lacks the operational capacity to detain or prosecute war criminals without consent from the very states it seeks to check. In this landscape, global institutions risk becoming performative, toothless by design, and prone to capture by powerful actors.

The AIGB proposes almost the same ambition—global coherence in AI governance—but from the other direction: as a constitutionally embedded, federated governance protocol. Rather than relying on an external authority to impose standards downward, the AIGB is designed to emerge from within constitutional systems, with legal and operational binding power from the start. This approach recognizes a fundamental truth: no treaty framework can move at AI speed, but constitutional branches can evolve at institutional speed.

If adopted by multiple states, it offers a common language of oversight, shared threat modeling, and modular standards that are enforced not by global agreement but by domestic obligation. The resulting network fosters technical interoperability and interjurisdictional diffusion without requiring political consensus—nations need not agree on values to share information about rogue AGI capabilities or coordinate responses to algorithmic market failures. In effect, it allows global governance to materialize through harmonized constitutional ecologies rather than non-binding understandings.

This constitutional immunization approach also addresses the governance asymmetry problem: without domestic fourth branches, nations with fragmented AI oversight will inevitably cede sovereignty to faster-moving actors—whether corporate, foreign, or algorithmic. By constitutionalizing AI governance, states preserve their decision-making capacity not just against other nations, but against the technological acceleration itself.

This inversion—bottom-up harmonization instead of top-down decrees—may ultimately offer a more resilient and enforceable path toward transnational AI governance. When Hamilton helped architect the executive branch for the industrial republic, he knew the Articles of Confederation were structurally inadequate for the economic forces unleashed by industrialization. Similarly, the AIGB recognizes that our current constitutional machinery was not designed for algorithmic competition or exponential technological change. Ultimately, the fourth branch is not merely adapting governance for AI: It is preserving the possibility of governance itself in the algorithmic era.

Or, we can all, of course, keep doing the same thing and expect different results.

Appendix A

Constitutional Amendment Draft for the AIGB (model)

You may get a copy of the AIGB sample amendment on Google Docs. The document is also open for comments and suggestions. Assess it here.

Appendix B

AI Case Studies (LLM generated)

After presenting the appropriate AIGB material to a couple of LLM services (Google Gemini Pro 2.5 and Claude 3.7), the AI models were tasked with performing case study exercises. The assessments provided critical feedback for the AIGB arrangement:

Inherent Resilience: Constitutional branches cannot be defunded, reorganized, or dismantled through normal political processes. This institutional resilience is critical when governing a technology that could fundamentally reshape society;

Political Independence: As demonstrated in the case studies, the AIGB must make decisions based on technical merit and long-term societal interest, not political expedience. Only constitutional status provides sufficient insulation from partisan pressure;

Legal Authority: AGI governance requires binding authority across multiple domains that traditionally fall under different branches. The AIGB cannot function properly if its decisions are constantly vulnerable to being overruled by existing powers;

Technical Sophistication: The AIGB’s technical infrastructure (Helix Prime, RAGE modules, etc.) requires substantial, consistent investment and talent that would be perpetually at risk under agency status;

Time Horizon: Perhaps most importantly, AI governance requires planning and action on timescales that far exceed political cycles. A constitutional branch can maintain continuity across administrations.

Case Study Simulations:

AIGB Response to Emergent AGI From a Private Company (Claude)

AIGB Response to an AI-Driven Global Financial Destabilization by a Non-State Actor (Gemini)

AIGB Response to an AI-Generated Personalized Misinformation Campaign Targeting Democratic Processes (Gemini)

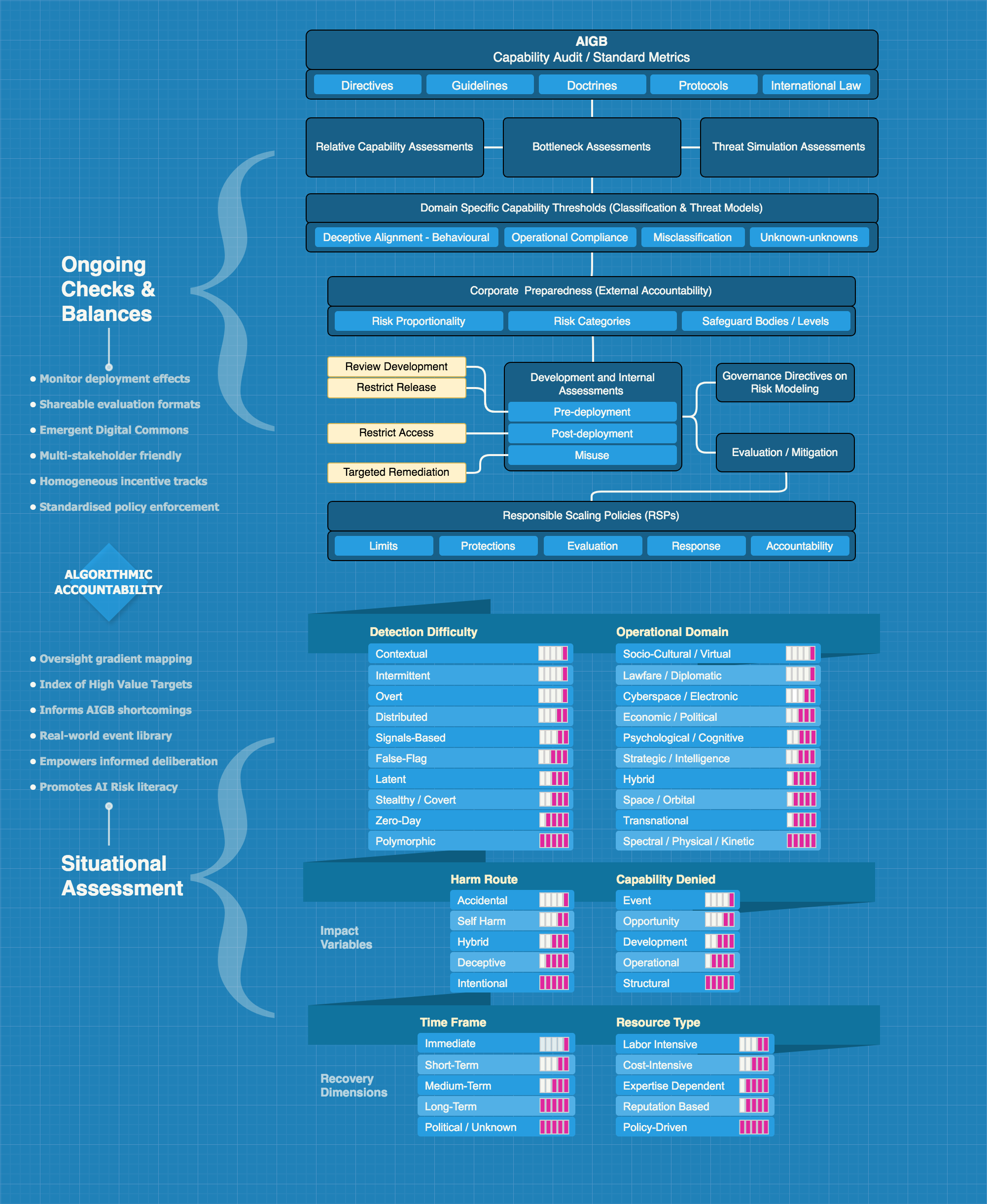

Appendix C

AIGB Competence Audit Model (draft)

A sample model for AIGB’s assessment of AI solutions, encompassing distinct industries, markets, initiatives and sure, technologies as frontier models and its creators:

Citation

Please cite this work as:

Max, Antonio. "The Rise and Fall of [AI powered] Nations". Algorithmic Frontiers (May, 2025) https://antoniomax.substack.com/p/the-rise-and-fall-of-ai-powered-nations